There is a wide range of different writing systems all around the world, but a large majority of them share one common ancestor: the ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs. From the Latin alphabet to the Arabic script, from Ethiopian characters to Mongolian writing, and probably even the South Asian systems, they all derive from the hieroglyphs used thousands of years ago in Egypt. The only major exceptions are Chinese and Japanese characters, and the Korean Hangul, along with some more minor and mostly modern scripts. So, how did this happen? How did some Bronze Age drawings evolve into most of the world’s writing systems? To find out, let’s start by going back more than five thousand years in the past.

From the hieroglyphs to the alphabet

The earliest recorded evidence of writing dates from around 3300 BCE, when the cuneiform script developed by the Sumerian civilization started emerging in Mesopotamia. The first Egyptian hieroglyphs appeared not much later. It is generally accepted by modern scholars that the ancient Egyptians developed their system independently, as there is no evidence of similiarities with cuneiform or direct influences by the Sumerians, but it is likely that the idea of expressing words with symbols spread into Egypt from Mesopotamia. Over the centuries, the Egyptian writing system evolved to include hundreds of hieroglyphs. Sometimes they were logograms, symbols that represent entire words, while other times they could be read phonetically, with different sounds or groups of consonants associated with them. This system was very complicated and a simpler and faster cursive form, known as hieratic, soon emerged and became the standard used in everyday life, while hieroglyphs were restricted to monumental inscriptions and more formal manuscripts.

Meanwhile, hieroglyphs and hieratic spread from Egypt to the surrounding regions. Some inscriptions found between the Sinai peninsula and ancient Canaan attest that simplified hieroglyphs were repurposed to write a different language some time bewteen 1850 BCE and 1550 BCE. This language was an ancestor of modern Hebrew and part of the Semitic family, which is distantly related to ancient Egyptian but still different enough to necessitate a reinvention of the symbols. The Proto-Sinaitic script might be the earliest example of an alphabet, a writing system in which symbols only describe sounds. To be more precise, the word “alphabet” is used, in a more narrow sense, for those systems that have separate symbols for both consonants and vowels. Thus, the Proto-Sinaitic script was actually the first abjad, a system that only (or almost exclusively) represents consonsants. Another type of script that is not a proper alphabet is the abugida, in which consonant-vowel sequences written as units may be modified to change or remove the vowel sound. For simplicity, I’m going to use the word “alphabet” in its looser meaning.

The direct descendant of the Proto-Sinaitic script is the Phoenician alphabet, an abjad that emerged in the Levant around 1000 BCE. As the Phoenician civilization thrived and expanded across the Mediterranean, so did their alphabet, helped by the simplicity of its phonetic nature and the small number of letters to remember, compared to the hundreds of complex hieroglyphs or cuneiform symbols. The Phoenician alphabet gave rise to two very influential writing systems: Greek and Aramaic. The Ancient South Arabian writing also originated from Proto-Sinaitic, later evolving into the Ge’ez script used to this day to write various languages of Ethiopia and Eritrea.

Phoenician letters started being adopted in Greece around the eighth century BCE. Most were used with the same sound value as in Phoenician, but this language had some guttural consonants that are common in the Semitic family and did not exist in Greek. However, the Greeks did not eliminate the letters associated with these sounds, instead changing their meaning and using them to represent vowels. For example, the Phoenician ‘ālep (𐤀), used for the glottal stop, became the Greek letter alpha (A, α) with the vowel sound [a]. By this point, the Phoenicians had sometimes used consonants to also indicate vowel sounds, but the Greeks were the first to use symbols only for the vowels, thus creating the earliest real alphabet in history. The Greeks also added some more entirely new letters to the alphabet.

Meanwhile, a separate script, known as Libyco-Berber alphabet, evolved from Phoenician in North Africa and was used to write ancient Berber languages. Today many languages of the Berber family use the Tifinagh abjad which branched from the ancient Libyco-Berber script with additions and alterations. A fully alphabetic Neo-Tifinagh script has been developed more recently but has only seen limited use.

Descendants of the Greek alphabet

As the Greek civilization spread around the Mediterranean with the founding of numerous colonies, their alphabet slowly replaced the Phoenician one as the most commonly used in the region. Local variations soon emerged as other peoples adopted the letters of the nearby Greek colonies. The most relevant of these is the Etruscan alphabet adapted from the one used by Greek colonists in Campania, Southern Italy. However, the Etruscan language was tipically written from right to left, so many letters were flipped compared to their Greek counterparts. Occasionally the Etruscan also used the boustrophedon style, alternating right-to-left and left-to-right text.

The Etruscan alphabet spread around the Italian peninsula becoming the most prominent of the various Old Italic scripts. Among the many peoples of Italy were the Latins, who adopted the Etruscan alphabet with a few differences as some letters were dropped and new ones were created. Also, over the centuries the direction of the text became fixed as being from left to right, flipping back the letters to the way they were written in Greek. Thus, the Latin alphabet, the most widespread writing system in the world today, was born. As the Romans conquered the Mediterranean region and large parts of Europe, the Latin script became the standard in the continent, replacing other descendants of Greek and Old Italic alphabets.

A notable example of European writing system that survived for a long time is the runic alphabet, that was used to write Germanic languages in Northern Europe. Evolved from Old Italic scripts, runes were widely used by Scandinavian peoples during the Middle Ages, but were ultimately replaced by Latin letters. During the age of European colonization, the Latin alphabet spread across the world and sometimes replaced older local independent writing systems such as the Mesoamerican scripts. Today the Latin alphabet is used by most countries in Europe, America, Sub-Saharan Africa, Oceania, and South-East Asia, often with regional variations.

While the Latin script became the standard in Western Europe during classical antiquity, the Greek language was still the lingua franca in the Eastern portion of the Roman Empire and influenced the evolution of writing systems across Eastern Europe and West Asia. A few new alphabets emerged in this region between the third and tenth century. The Coptic alphabet was based on the Greek system and influenced by the Egyptian Demotic script, an evolution of the earlier hieratic. The Coptic script was used for centuries in Egypt and Nubia, replacing the Demotic system and its descendant, the Meroitic alphabet. Today the Coptic language is functionally extinct, but it is still used by the Coptic Orthodox Church as a liturgical language, along with its alphabet. Another extinct writing system deriving from Greek is the Gothic alphabet that was used for centuries by the Goths all across Europe and slowly faded away during the Middle Ages.

Two more scripts emerged in the Caucasus around the fifth century: the Armenian and Georgian alphabets. These were created almost simultaneously and were likely modeled after the Greek alphabet with some influences by other writing systems of West Asia such as the Aramaic and Syriac ones. After undergoing centuries of evolution, the Armenian and Georgian alphabets are used to this day to write those two languages.

During the ninth century, the Glagolitic script was developed by Saint Cyril and Saint Methodius, two Byzantine monks that were sent to spread Christianity among Slavic peoples of Central and Eastern Europe. This system only saw limited adoption, surviving through the Middle Ages only in Croatia, before slowly declining. Instead, a different script was introduced for Slavic peoples: the Cyrillic alphabet, named in honor of Saint Cyril and created around the mid tenth century in Bulgaria. Cyrillic soon replaced Glagolitic, and it is now one of the most widespread alphabets in the world, being the official or co-official script in Russia and most of the former Soviet republics, as well as Bulgaria, Serbia, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Bosnia and Herzogovina, and Mongolia.

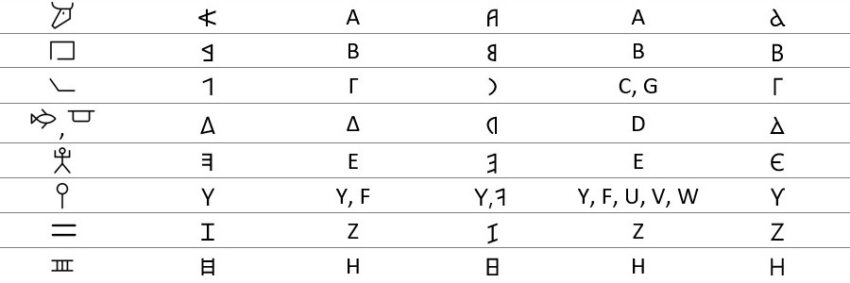

Comparison of select writing systems deriving from Egyptian hieroglyphs through Greek or directly from Proto-Sinaitic (not all graphemes of each alphabet are represented). It is generally believed that the Greek Φ and Χ have no connection with the Phoenician 𐤒 and 𐤕, despite the similarities, so they are listed separately.

Descendants of the Aramaic alphabet

While Greek and Latin were the most widespread languages in Europe, the ancient Middle East adopted Aramaic as a lingua franca. Thus, the Aramaic abjad, that evolved from the Phoenician one, became the standard script from the Levant to Central Asia thanks to the conquests of the Achaemenid Empire. Many different modern writing systems developed from the Aramaic alphabet, including almost all of those used today in the Middle East and South Asia.

Among the earliest writing systems to branch out from the Aramaic one is the Hebrew abjad. While an older Paleo-Hebrew alphabet evolved directly from the Phoenician one, later becoming the Samaritan script, the modern Hebrew alphabet comes from an adaptation of the Aramaic system. Meanwhile to the south, the Aramaic alphabet evolved into the Nabataean one which spread across the Arabian peninsula, giving rise to the current Arabic script. This system is among the most widespread today, being adopted throughout the Muslim world across North Africa, the Middle East, and parts of Central, South and South East Asia, and it is used, with small variations, by languages of various different families.

Another writing system that emerged from the Aramaic one in the Middle East is the Syriac script. This alphabet was common in the Early Middle Ages before being replaced by the Arabic script, but it survives to this day to write a number of Neo-Aramaic languages. The Syriac writing system spread not only across the Middle East, but also in Central Asia, where it evolved into the Sogdian and then the Old Turkic script. As the Hungarian people migrated from the steppes of Central Asia into Europe, they brought with them their version of this script, known as Old Hungarian, but they later adopted the Latin alphabet and the traditional system fell out of use. The Uyghurs were another people of Central Asia that adopted the Old Turkic alphabet, which evolved into the Old Uyghur one. This system was later used by the Mongols, eventually becoming the modern Mongolian script and the closely related Manchu alphabet. In Iran the Aramaic system evolved into the Pahlavi and later Avestan script, which were the most widespread in ancient Persia and Afghanistan before the Arabic alphabet became the standard with the Muslim conquest of the area. The Mandaic alphabet also evolved from the Aramaic one and it is still used today, although only for liturgical purposes by a small numbers of Mandaic speakers between Iraq and Iran.

The Aramaic language spread all the way to modern-day Pakistan, where the Khartosthi script, derived from the Aramaic one, was used in ancient times. Less certain is the connection between Aramaic and the Brahmi script of India. During the Bronze Age, the Indus Valley Civilization used some symbols now known as Indus script, which is still undeciphered and might not constitute a full writing system. There is no definitive evidence for a connection between these symbols and the Brahmi script, which was instead very likely inspired and influenced by the Aramaic alphabet or its descendants.

The Brahmi script was used to write Sanskrit, once the language of religion and culture throughout all of South and South East Asia, and so this writing system gave rise to many different alphabets in this region. These are collectively known as Brahmic scripts. While most of the other scripts deriving from the Aramaic one are abjads, all the Brahmic ones are abugidas. Among these, the most widespread today are Devanagari, used to write the Hindi language and many other idioms from the region, and the Bengali-Assamese script, most commonly associated, as the name suggests, with the Bengali and Assamese languages. Both of these writing systems are part of the Northern Brahmic subfamily, which developed from the Gupta script used during the age of the Gupta Empire in Northern India, and also includes many more alphabets such as the Gujarati, Gurmukhi, Odia and Tibetan ones. Meanwhile, the Southern Brahmic subfamily evolved from the Tamil-Brahmi abugida in Southern India, which also spread to South East Asia, and includes the Telugu, Tamil, Kannada, Mon-Burmese, Malayalam, Thai, Lao, Sinhala and Khmer alphabets, among others. Even the Canadian Aboriginal syllabics can trace their origins to the Brahmi script, and thus ultimately the Egyptian hieroglyphs, as they were developed during the nineteenth century based on the Devanagari system.

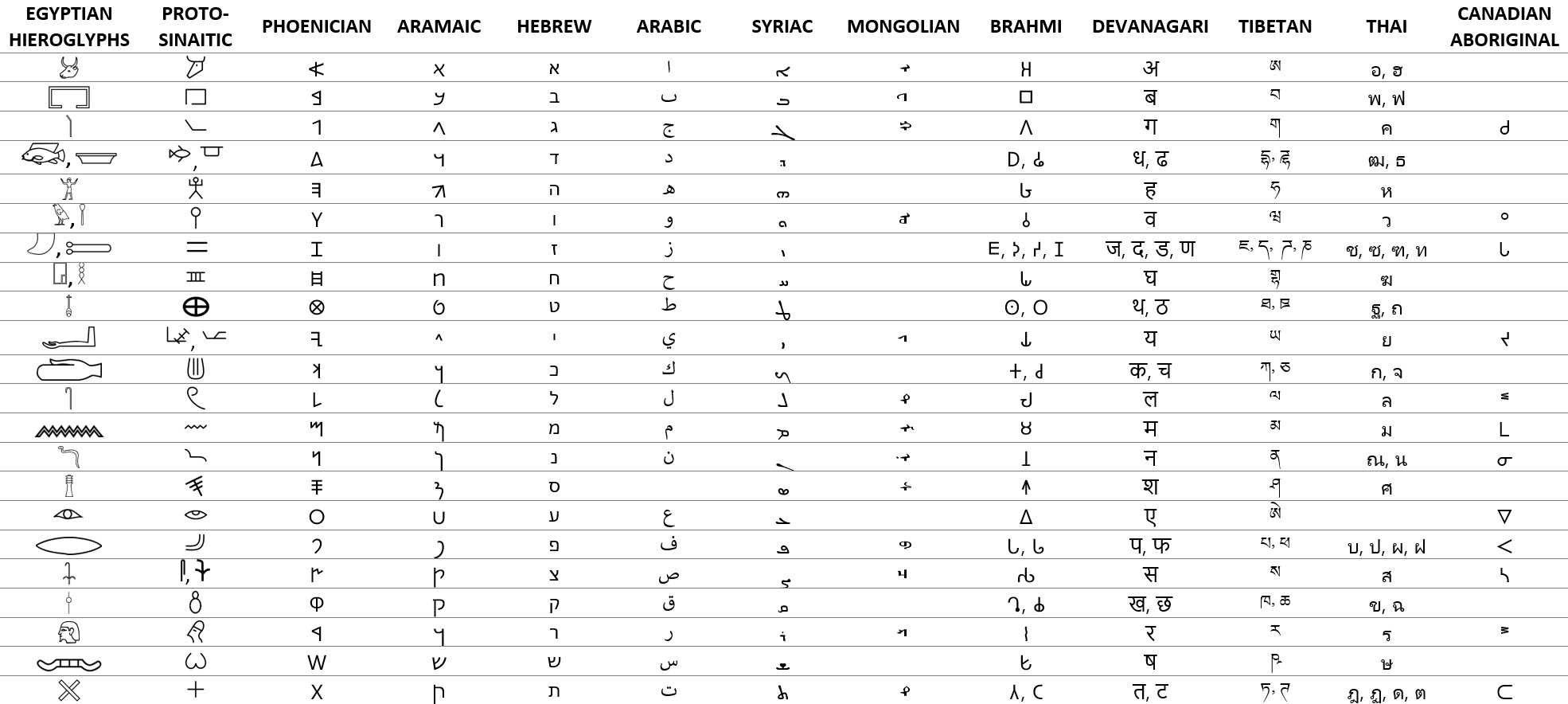

Comparison of select writing systems deriving from Egyptian hieroglyphs through Aramaic (not all graphemes of each alphabet are represented).

Independently developed systems

So now the question is: which writing systems did not evolve from the Egyptian hieroglyphs? Clearly the Chinese characters and Japanese kanji, both of which derived from the ancient oracle bone script of Bronze Age China. The Japanese hiragana and katakana syllabaries also share the same origin, as they were developed as a simplified form of kanji. The Korean Hangul has a much different history, being invented from scratch in 1443 by King Sejong or his scholars to replace the difficult Chinese characters with a simpler system. Meanwhile Thaana, the writing system of the Maldivian language, is a borderline case, as its symbols come from Arabic and Indic numerals, not from letters, so although it is not completely original, it does not really derive from any other alphabet.

Over the past two centuries, new writing systems have been developed for various languages across the world that did not have one. Some of these have been based on or inspired by the Latin, Greek, Cyrillic, Arabic and Brahmic alphabets, such as the Cherokee syllabary in North America and the N’Ko script in West Africa, while others are fully independent. Prominent modern writing systems in Africa include the Adlam script of the Fula language and the Vai syllabary, which might have been inspired by the Arabic and Cherokee systems respectively. The Mandombe script used in some languages of the Democratic Republic of the Congo was instead supposedly “revealed in a dream” to its creator. A few more modern constructed writing systems can be found across Africa, Asia, and Oceania, but almost all of them have only seen a limited adoption, usually by not more than a few tens of thousands of people, and often just as an alternative to more common scripts. Among the most successful examples are the Ol Chiki, Warang Citi, and Sorang Sompeng scripts, respectively used for the Santali, Ho, and Sora languages, all part of the Munda family in Northeast India.