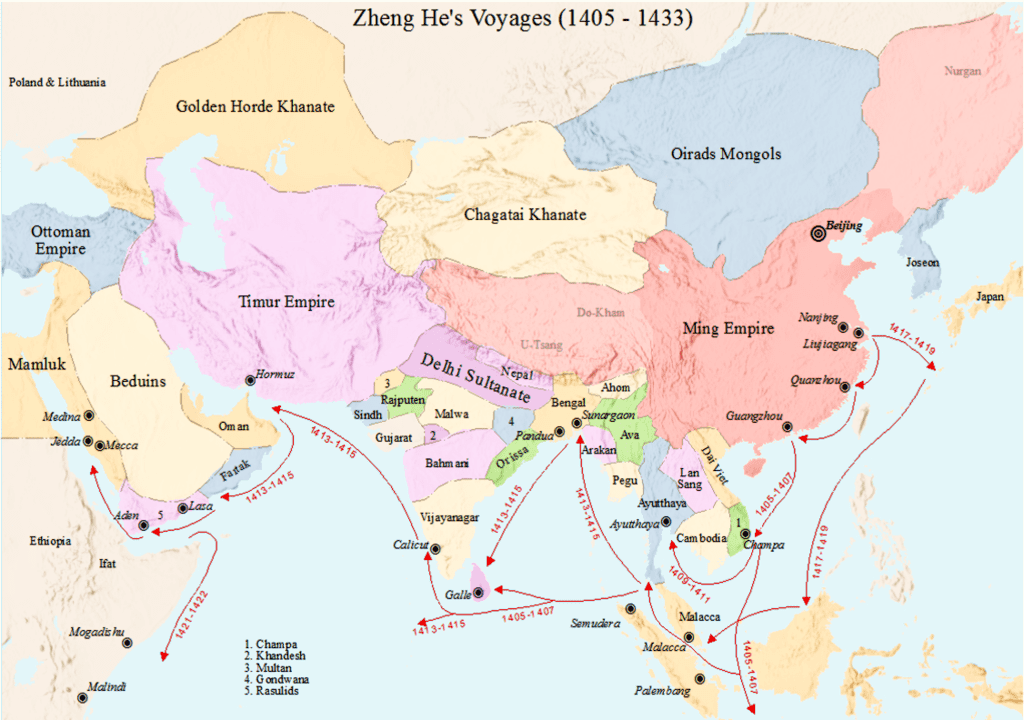

Between the fifteenth and eighteenth century, European explorers and colonizers sailed the oceans, expanding from their continent to the entire world during the so-called Age of Discovery. However, decades before the Spanish ships crossed the Atlantic Ocean to reach the Americas, the Chinese Empire, ruled by the Ming dynasty, saw its own age of exploration. From 1405 to 1433, seven maritime expeditions known as the “treasure voyages” sailed around the South China Sea and the Indian Ocean, reaching Southeast Asia, India, the Arabian Peninsula, and Africa. These voyages were carried out by huge fleets, with very large and heavily-armed ships that carried treasures and riches, projecting the diplomatic and military power of the Ming Empire throughout the region, bringing many countries into the Chinese sphere of influence, sometimes by force. The history of the Ming treasure voyages is closely related to the internal affairs of China and the life of the admiral who led the expeditions: Zheng He, a Muslim eunuch and former slave.

Zheng He and the Yongle Emperor

Zheng He was born as Ma He in 1371 from a Muslim family living in the modern-day province of Yunnan, China. At the time, Yunnan was ruled by loyalists of the fallen Mongol Yuan dynasty, which was deposed by the Ming in 1368. Zheng He himself was a descendant of a Mongol governor of Yunnan named Ajall Shams al-Din Omar. The Ming forces attacked the Yuan remnants in Yunnan in 1381, and Zheng He was captured and later castrated, becoming a eunuch servant of Zhu Di, Prince of Yan. Zhu Di was at the time the ruler of Beijing, near the northern frontier, and often launched military campaigns against the Mongols. Zheng He took part in the expeditions as a soldier and, over the years, became a trusted confidant of the prince, and received a formal education.

Due to his growing power, Zhu Di was considered as a rival by the ruling Jianwen Emperor, who ordered his arrest in 1399. The Prince of Yan responded by leading a rebellion against the imperial court, which evolved into a three-year-long civil war known as the Jingnan campaign. Througout the war, Zheng He assisted his master as one of his military commanders and, after the successful rebellion, Zhu Di was crowned as the Yongle Emperor in 1402. The new emperor promoted his favorite eunuch, still called Ma He, to Grand Director of the Directorate of Palace Servants, and gave him the new surname Zheng in 1404, a reference to his victory against the enemy forces at Zhenglunba, the city reservoir of Beijing, during the Jingnan campaign five years earlier.

Statue of Zheng He in Nanjing, China (left) (Vmenkov, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0) and a portrait of the Yongle Emperor (right).

Projecting power: the first three treasure voyages

The Yongle Emperor wanted to expand the power of China and one of his primary objectives was to establish imperial control over the Indian Ocean trade, while also extending the tributary system of the Empire. He ordered the construction of a huge fleet, which included warships as well as trading and support ships, and placed Zheng He in command. However, according to the historical text History of Ming, the heavily-armed first expedition might have instead been ordered just to find the Jianwen Emperor, the deposed predecessor of the Yongle Emperor, who was believed to have fled to Southeast Asia.

Whatever the reason behind it, the first voyage departed from the imperial capital Nanjing on July 11, 1405, after offering sacrifices and prayers to Tianfei, the tutelary deity of seafarers, to which Zheng He was devoted in his unique syncretism between Islam and Chinese folk religion. The first expedition brought gifts and imperial letters in its 62 treasure ships, while 255 vessels took part in the voyage. It is not clear if these 255 are all the ships or just the support vessels, the second case would raise the total number of ships taking part in the voyage to 317. The ships were crewed by almost 28,000 men.

The fleet reached Champa, in modern-day Vietnam, and continued south in 1406 to Malacca and then Java, before returning to the north and crossing the Strait of Malacca. The expedition visited northern Sumatra and the Andaman Islands, and then sailed the Indian Ocean to Ceylon, now Sri Lanka, where the local king Alakeshvara was unfriendly to the fleet. After departing Ceylon, the voyage reached its final destination of Calicut, on the southwestern coast of India. The fleet may have stayed for a few months in Calicut before their return trip in 1407, during which Zheng He defeated the pirates led by Chen Zuyi who were occupying Palembang, on the island of Sumatra. After the capture and execution of Chen Zuyi, the Ming sent trusted civil servant Shi Jinqing to rule Palembang, gaining access to a strategic port on the Strait of Malacca. The expedition returned to Nanjing on October 2, 1407, and immediately a second voyage was ordered by the Yongle Emperor, departing in late 1407 or early 1408 with 249 ships.

The second voyage followed a similar path as the first one, stopping in Champa, Siam, Java, Malacca, and Sumatra, but the expedition avoided Ceylon before reaching Calicut. There, the Ming established a friendly relationship with the local king, while there was some tension between China and the Majapahit Empire of Java after the Javanese killed some members of a Chinese embassy. The dispute was settled when Majapahit apologized and sent gold to the Ming as compensation, restoring diplomatic relations.

The second expedition returned to Nanjing in the summer of 1409, but a third one had already been ordered a few months earlier, so Zheng He again departed with his fleet that October. After following the usual route, the Ming expedition landed in Ceylon either in 1410 or 1411, and deposed with military force the ruler of the local Kingdom of Kotte, Alakeshvara, who opposed the Chinese presence years earlier. The Ming fleet, counting over 27,000 men, defeated the larger Sinhalese army of 50,000 troops, and put their ally Parakramabahu VI on the throne of Kotte. The third voyage ended in July 1411, with the fleet returning to Nanjing.

Model of a treasure ship in the National Museum of China in Beijing (Gary Todd, Wikimedia Commons, CC0 1.0).

China dominates the Indian Ocean trade

The fourth expedition departed from Nanjing in the autumn of 1413, with interpreters and translators in order to facilitate trade with the Muslim countries. The fleet followed the familiar route to Calicut before sailing beyond India to reach the Maldives and Lakshadweep Islands, and then Hormuz, in modern-day Iran. After trading with the locals, the expedition stopped in Sumatra during their return trip. There, the Ming troops attacked and deposed Sekandar, usurper of the rightful ruler of the Samudera Pasai Sultanate. After once again affirming the Chinese influence in the Strait of Malacca, the fleet returned to Nanjing in August 1415.

During the time of the fourth expedition, the Yongle Emperor was fighting the Mongols on the northern border, and only returned to the capital in late 1416. Upon its return, a great ceremony was held and the emperor received the ambassadors of eighteen countries, each one bringing gifts to him. The Yongle Emperor immediately announced a fifth voyage to escort home the ambassadors and send gifts to their countries.

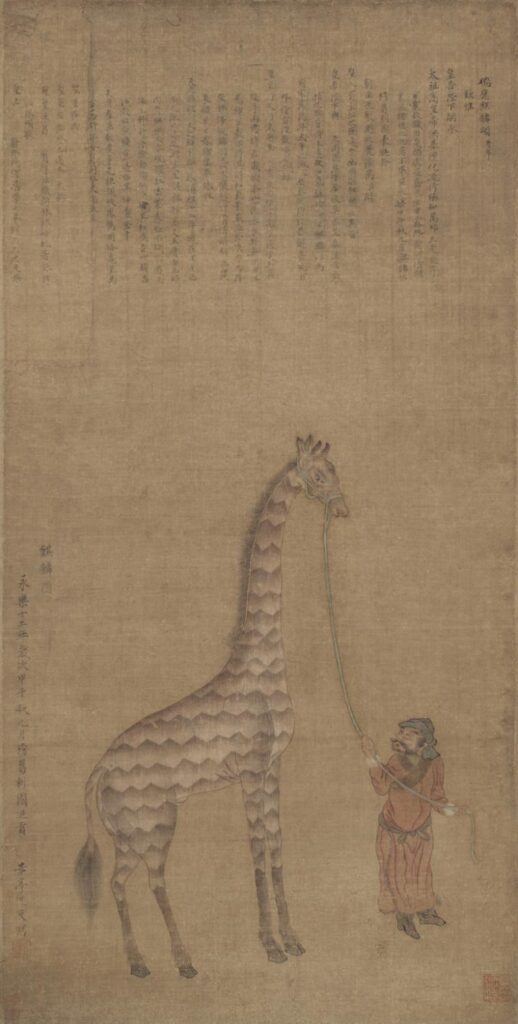

The fifth voyage went even further than the fourth one. Departing in the autumn of 1417, the fleet again reached Hormuz before continuing to Aden, on the Arabian Peninsula, Mogadishu and Barawa, now both in Somalia, and finally arriving in Malindi, in modern-day Kenya. The stop at Aden in 1419 is well documented in local records, and describes splendid and rich “dragon ships”, filled with treasures. The sultan of the Rasulid dynasty, that ruled Yemen at the time, sent back gifts and tributes and submitted to the Ming in exchange with protection against the Mamluk Sultanate of Egypt. When the fleet returned to China in August 1419, it brought many exotic animals such as lions and cheetas from Yemen, giraffes from Somalia, and also camels, zebras, rhinoceroses, ostriches, antelopes, and leopards.

In 1421 an order was issued for the sixth voyage which, similarly to the previous one, was aimed at returning the foreign ambassadors home with more gifts, mostly silk products. Departing in November 1421, this expedition arrived in Ceylon and then split into smaller groups, with each reaching different destinations they previously visited in India, the Maldives, Hormuz, various Arabian states, and the Eastern African coast. After getting the whole fleet back together, the expedition stopped in Siam before returning to China in September 1422.

Depiction of a giraffe gifted by Bengali envoys to the Yongle Emperor.

The last treasure voyage

The voyages were temporarily halted after the sixth one, as funding was diverted to the ongoing campaigns against the Mongols in the North. In 1424, Zheng He sailed to Palembang on a short diplomatic mission, but when he came back he found out that the Yongle Emperor had died and was succeeded by his son, the Hongxi Emperor. The new emperor opposed the treasure voyages and officially cancelled any plan for future expeditions. Zheng He was nominated Defender of Nanjing and kept his fleet, but only as part of the capital’s garrison. However, the Hongxi Emperor died in May 1425 and was succeeded by his son, the Xuande Emperor. Under the new ruler Zheng He initially kept his position in the capital, even supervising the restoration of the Great Bao’en Temple in the city, and was then ordered to lead a seventh voyage to the Indian Ocean in 1430.

The seventh, and last, treasure voyage departed from Nanjing on January 19, 1431, with the goal of demanding tributes and submission from foreign countries. After following the coast of China, the fleet reached Vietnam, before continuing towards Surabaya, Palembang, and Malacca. The expedition stopped in Semudera, in northern Sumatra, where the fleet was divided in two. While the main group crossed the ocean to reach Ceylon and Calicut, a smaller squadron visited Chittagong, Sonargaon, and Gaur in Bengal, before reuniting with the other ships in Calicut.

The itinerary of the expedition is not clear after Calicut, some sources report only a visit to Hormuz, while others suggest that at least some of the ships may have sailed to East Africa and the Arabian coast, even reaching Mecca. Nevertheless, the fleet returned to China in September 1433. Sources are conflicting also on the death of Zheng He, that might have occurred either during the seventh voyage or shortly afterwards, in 1435. This marked the end of the Ming treasure voyages. Why exactly no more expeditions were ever ordered is not clear, but it might have been caused by bureaucrats, traders, and other powerful individuals that wanted to protect their own economic interests in China, opposing a total control of the government over foreign trade.

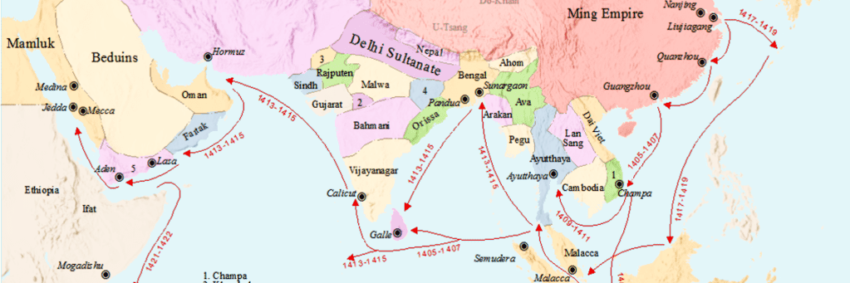

Map of the voyages of the treasure fleet of Zheng He (SY, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0).

The decline of the Ming Empire

After the treasure voyages, the Ming Empire, the most powerful naval power in Asia, gradually declined as the tributary system broke down and the government lost his maritime monopoly. The Indian Ocean and South China Sea trade flourished for some time even after the voyages stopped, but then the Ming started turning from foreign to local commerce, leaving the seas. In the following decades, the voyages were described by civil officials as wasteful, costly, exaggerated, and even contrary to Confucian principles. The absence of the Chinese influence in the Indian Ocean left a power vacuum in the region for decades, until the European explorers started taking control of the trade in the area at the end of the fifteenth century. However, the memory of the Ming treasure voyages remained in the regions they visited for much longer.

It is interesting to wonder what could have happened if the Ming expeditions continued and traveled further. Maybe Chinese fleets could have crossed the Cape of Good Hope into the Atlantic Ocean. Maybe they could have reached and even colonized Australia centuries before the Europeans. What if they decided to sail east across the Pacific Ocean, setting foot on the western coast of America? Could there have been a war between the Ming Empire and the Western powers for control over the Indian Ocean, or even global, trade? We will never know, but this possibility remains one of the most fascinating what-ifs in world history.