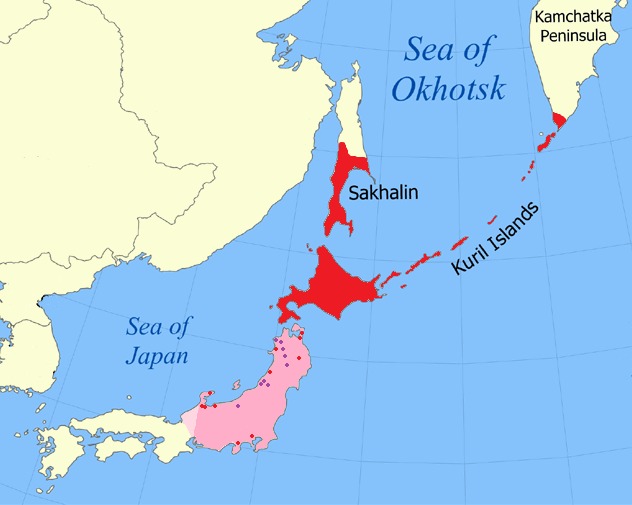

Japan is one of the most ethnically and culturally homogeneous countries in the world, as almost the entire population identifies as Japanese. However, there are a few minorities and two indigenous peoples: the Ryukuans in the Ryukyu Islands to the south, and the Ainu in northern Japan. After centuries of colonization and forced assimilation, only around 25,000 Ainu remain today, but there might be up to 200,000 people of Ainu descent. The Ainu today live mostly in Hokkaido, the northernmost of the four major islands of Japan, with other Ainu communities residing in the Tōhoku region. A few thousands of Ainu also in live in a few regions of Russia near Japan, such as Sakhalin, the Kuril Islands, Kamchatka, and Khabarovsk Krai.

Area historically inhabited by the Ainu people (in red) and suspected former range (pink) (Kwamikagami, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0).

The Ainu have a long a history that stretches all the way back to prehistoric Japan. During the Jōmon period, between around 14,000 BCE and 300 BCE, Japan was inhabited by the Jōmon people, a people that originated in East Asia before moving to the Japanese archipelago. Starting from around 300 BCE, the Jōmon in southern and central Japan began to become assimilated to the Yayoi people, who immigrated to the Japanese archipelago from East Asia. The modern Japanese, also called Yamato people, are descendants of both the Yayoi and the Jōmon people. However, northern Japan was less influenced by the arrival of the Yayoi, and mostly retained its Jōmon culture.

By the 5th century CE, the Jōmon people of northern Japan had evolved into the Emishi. The Emishi lived mostly in northern Honshu, and resisted the rule of the Japanese emperors for centuries. However, over time the Japanese expanded their rule to the north, and by the 9th century they had conquered all of Honshu. Some of the Emishi submitted to the Japanese, but others instead moved more north, to the island of Hokkaido. While the exact relationship between the two groups is still unclear, it is now generally accepted that the Emishi are either the ancestors of the modern Ainu or they share a common ancestor with them. The society that developed in Hokkaido between 700 and 1200, known as Satsumon culture, might have been a transition between Emishi and Ainu or a merger of the two cultures that resulted in the rise of the modern Ainu.

By the 13th century, the Ainu had developed their own unique culture in Hokkaido and the surrounding islands, living as hunter-gatherers and following a religion based on nature. The Ainu expanded to Sakhalin, fighting against the indigenous Nivkh people, who were pushed to the northern half of the island. The Nivkh allied with the Mongols, who made several incursions into Sakhalin and fought numerous times with the Ainu. The Ainu resisted and even launched a counterattack on the Asian mainland, but in the end they were forced to submit to the Mongols in 1308, becoming tributaries of the Yuan dynasty of China. The Yuan were later replaced by the Ming, but the Ainu remained tributaries of China.

Meanwhile, the Japanese had established an outpost in the Oshima Peninsula, the southernmost part of Hokkaido, and came into conflict with the Ainu as the settlement expanded. The Japanese defeated the Ainu in 1457, and in 1590 the Matsumae clan was charged with ruling over the newly established Matsumae Domain, a Japanese territory which gradually expanded north from the Oshima Peninsula. The Matsumae clan were given exclusive rights to trade with the Ainu, but their role was mostly defending Japan from the Ainu and subjugating them.

After the Qing dynasty replaced the Ming dynasty in China, the new rulers began demanding tributes from the peoples of Sakhalin, including the Ainu. The Japanese were also setting their sight on the island, and attempted a colonization of Sakhalin in the 17th century. The Ainu rebelled to the Japanese presence in Hokkaido a few times, most notably between 1669 and 1672, and again in 1789, but they were defeated in both occasions. By the early 19th century, the Japanese had expanded their influence to all of Hokkaido, the Kuril Islands, and the southern half of Sakhalin, all areas inhabited by the Ainu, which by this time had stopped paying tributes to the Qing dynasty. The Matsumae clan was nominally ruling over all these areas, but they didn’t really govern or protect the Ainu. Instead, they used them to obtain Chinese silk, which they sold as Matsumae’s product, increasing their prestige.

Ainu people in Hokkaido in 1904.

However, the Tokugawa shogunate took direct control of southern Hokkaido, and in 1807 they proclaimed Japanese sovereignty over Sakhalin. Japan also began to colonize these areas more strongly, separating Ainu women from their communities and forcing them to marry Japanese men. Ainu men were instead deported and forced to work under Japanese merchants. These policies of forced assimilation, along with the spread of smallpox, caused the Ainu population to drop significantly in the 19th century, from around 80,000 to less than 20,000 people.

At the same time Russia was colonizing the Far East, and by the 1840s they had reached Sakhalin. In 1855, Japan and Russia signed the Treaty of Shimoda, which stated that the Russians would stay in the north of the island while the Japanese would occupy the southern half, without a defined border. The treaty also divided the Kuril Islands between the two countries. Fearing a possible Russian invasion, Japan began expanding their northern defences and the development of Hokkaido, making the assimilation programs on the Ainu even more brutal.

In 1868, the Meiji Restoration overthrew the Tokugawa shogunate and established the Empire of Japan. Some military officials of the shogunate fled to Hokkaido, and in 1869 they established the Republic of Ezo. After a few months of resistence, Japan took control of Hokkaido once again, and officially annexed the island into Japanese territory. The new Japanese government invested heavily in developing the island, and began stripping the Ainu of their lands to give it to Japanese settlers.

In 1899, the Hokkaido Former Aborigines Protection Act prohibited the Ainu from fishing and hunting, removing their main source of subsistence. The act also forced them to assimilate and leave their traditional lands to be relocated in the inhospitable interior of Hokkaido. The Meiji government tried to completely eradicate Ainu culture and language, which was banned, and the Ainu were forced to take Japanese names. The same rules were also imposed on the Ainu of Sakhalin after Japan annexed the southern half of the island in 1905. The discriminatory practices caused the Ainu to have lower income and education levels than the Japanese, and the assimilation programs resulted in the modern Ainu being almost indistinguishable from the Japanese.

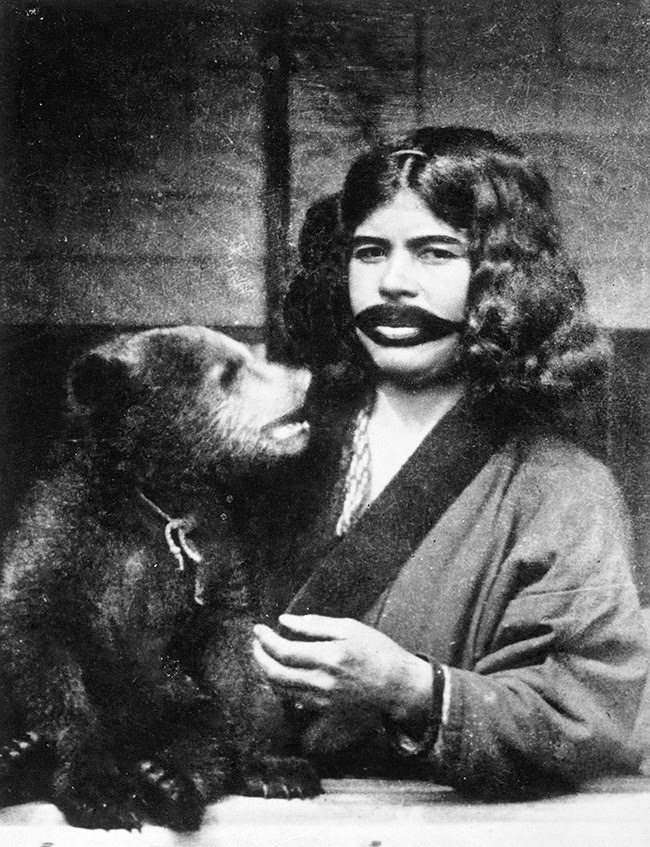

An Ainu woman in 1922 with the traditional mouth tattoos and a bear.

After World War II and the fall of the Empire of Japan, successive governments tried to portray Japan as a monocultural state, denying the existence of more than one ethnic group in the country. The discrimination of the Ainu continued, and in 1978 a new controversy arose when some Ainu landowners refused to relinquish their properties to allow the Japanese government to build a dam on their land. The Ainu won the legal battle in 1997 and, for the first time in Japanese history, the rights of the Ainu were recognized. This soon led to the abolition of the Hokkaido Former Aborigines Protection Act, which was still in effect. In 2008, the National Diet of Japan passed a non-binding resolution calling for the recognition of the Ainu as an indigenous people. The law was only passed in 2019, finally giving the Ainu legal recognition in Japan. However, many Japanese politicians still claim that Japan has one single ethnic group.

Today, most of the unique traditions of the Ainu are almost extinct. Ainu men traditionally have long beards, as they don’t shave at all after a certain age, while the women instead used to have large black tattoos around their mouths. However, these customs have been almost entirely abandoned now. The Ainu language, an isolated language with no relation to Japanese or any other language currently spoken, is critically endangered. There are currently only a handful of native Ainu speakers, but a movement to revitalize the language is expanding, with an increasing number of second-language learners.