If you look at different maps of Central Asia, you can notice that a large lake placed between the Caspian Sea and the Himalayan Plateau keeps changing shape. Sometimes it is very large and it has an almost round outline, while some other times it has nearly vanished, with only two smaller bodies of water instead. The latest satellite photos reveal that the second case is more accurate, with the lake almost entirely gone. What happened here? One of the worst environmental disasters in human history. The disappearance of the Aral Sea, in a few decades turned from a large lake into a barren desert.

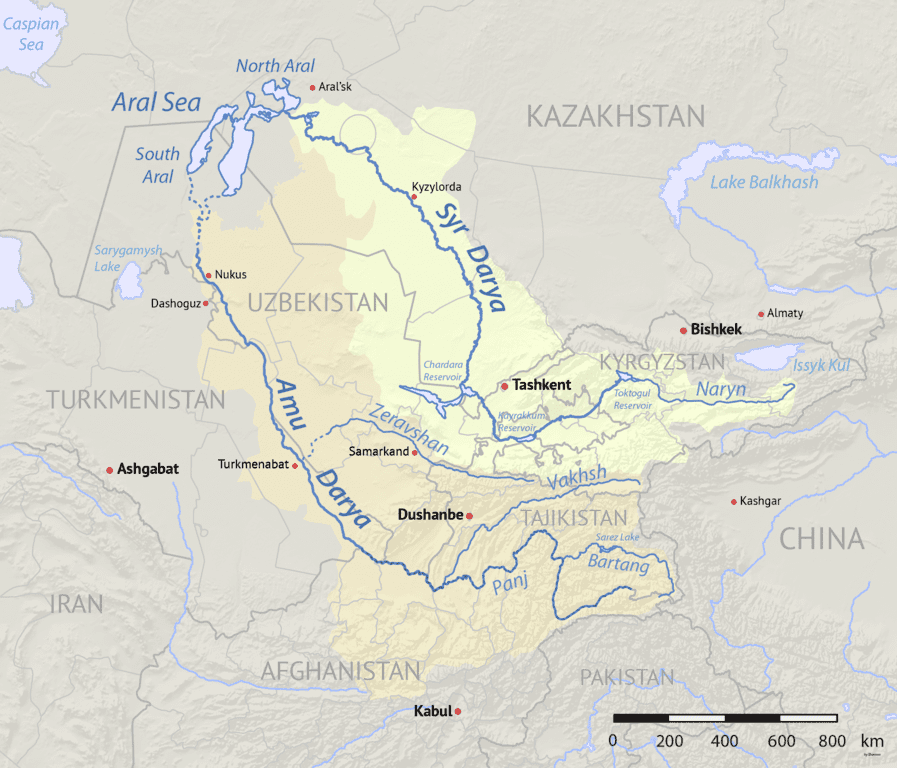

Located at the border between Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, the Aral Sea was once the fourth largest lake in the world, with an area of approximately 68,000 km2, larger than Lake Huron in North America and only slightly smaller than Lake Victoria in Africa. This endorheic basin was for millennia a reference point for the nomadic peoples of the Central Asian steppe, and was known since antiquity by both Western and Eastern explorers as the final outlet for two large rivers in the region: the Amu Darya in the south, and the Syr Darya in the north. The two rivers, which were historically called respectively Oxus and Jaxartes by the Ancient Greeks and Romans, flow from the Pamir and Tian Shan mountains through the fertile valleys of Bactria and Fergana before traversing the arid region between modern-day Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan, finally ending up in the Aral Sea.

Because of their position, locals began using the water of the two rivers to irrigate the desolate area and gain more agricultural land. The diversion of the water, along with differing precipitation patterns led, over the centuries, to a fluctuation of the level of the lake, but without impacting too much the whole system. During the nineteenth century, the Russians were expanding their influence in Central Asia and settled the area around the Aral Sea, establishing fishing companies and steamer navigation services in the lake and the two large rivers that flowed into it. The development of the area continued through the decades and also after the Soviet Union replaced the Russian Empire.

Watershed of the Amu Darya and Syr Darya rivers, that flow into the Aral Sea crossing Central Asia (Shannon1, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0).

The story of the Aral Sea changes drastically after World War II, when Stalin’s “Great Plan for the Trasformation of Nature” was proposed by the Soviet leader. The plan included a series of projects aimed at improving the agricultural output of Central Asia and provide more food for the whole country, often affected by harsh famines. While some of the plans were abandoned after Stalin’s death in 1953, in the 1960s the Soviet government implemented some of the projects for Central Asia, diverting the water of the Amu Darya and Syr Darya to irrigate new cotton plantations in the arid region.

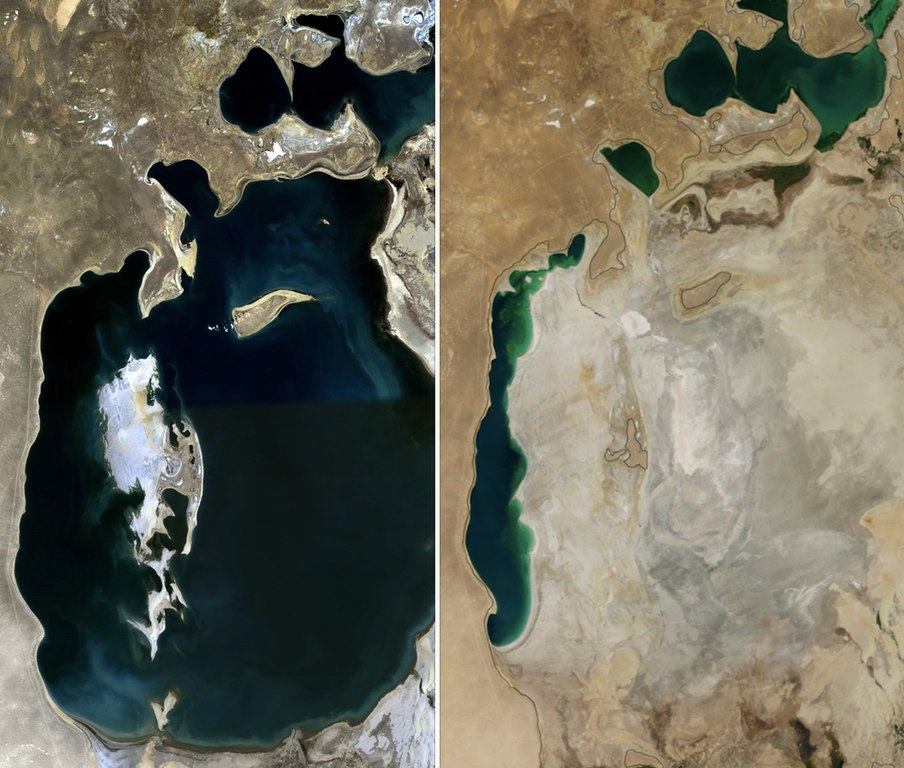

The canals built here were inadequate and most of the diverted water evaporated in the desert before reaching the agricultural lands, leading to more and more water being taken from the rivers and subtracted from the lake. This spelled disaster for the Aral Sea, that was already shrinking by the late 1960s, and by the 1980s its level was falling by almost one meter per year. Anyway, the project was deemed necessary and the lake’s disappearance inevitable by the Soviet higher-ups. Almost no effort was made in order to save the Aral Sea and the fishing villages on its shore turned into towns in the middle of a desert, while Uzbekistan became the world’s largest exporter of cotton. By 1987, the Aral Sea split into a small northern portion and a larger southern one.

Also, Vozrozhdeniya Island, located in the middle of the lake, was used since the 1930s as a site to test biological weapons and store dangerous agents. In 1971, an accidental release of variola virus from the facility caused a smallpox outbreak, with ten people infected and three deaths. The complex was abandoned in 1992 and the village of Kantubek, which hosted scientists and employees of the base, is now a ghost town.

The fall of the Soviet Union didn’t change much for the Aral Sea, with bad agricultural practices, waste of water, pollution, and chemical spills continuing for years. In the early 2000s, the southern portion split further into a western and eastern lake, as the formerly small Vozrozhdeniya Island became first a peninsula and then part of the mainland. In 2005 Kazakhstan built a dam between the northern and southern Aral Sea, allowing some surprising recovery in the northern portion. The water level here rose from 30 meters in 2003 to 42 meters in 2008, leading to a partial revival of the fishing industry. The Kazakh government announced in 2021 a plan to plant trees in the drained areas of the former lake in order to stop dust storms.

Meanwhile, the south-eastern portion of the lake is now basically extinct and the south-western one is mostly abandoned and it is slowly shrinking, with only some excess water periodically allowed to flow in from the northern part. The use of water from the Amu Darya to irrigate cotton plantations in Uzbekistan continues, while the drained area is being explored since 2006 in search for oil, gas, and other resources.

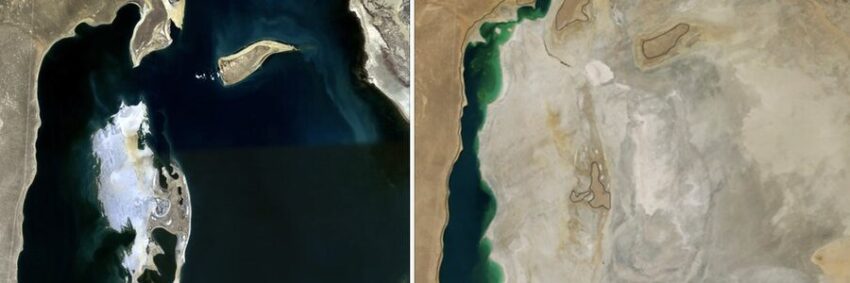

Satellite images of the Aral Sea in 1989 (left) and 2014 (right).

As a result of this environmental disaster, the Aral Sea ecosystem collapsed. It originally included a diverse array of species of fish and invertebrates, some of which native only to this lake. Now some of these species are locally extinct and, while the North Aral Sea saw some recovery of its fauna, the dam system blocks migration to the southern portion. The shrinkage of the lake also drastically increased the salinity in the remaining parts, killing many freshwater species, and the release of toxic chemicals due to weapons testing left the region extremely polluted. Plants and livestock absorbed these chemicals into their systems and are now too dangerous to be consumed, while dust storms keep spreading the pollutants around. People in the area suffer from high rates of respiratory and digestive illnesses, cancer, and tubercolosis. The Aral Sea region also sees some of the highest rates in the world of children born at low birthweight and with abnormalities, in an area already lacking in health infrastructure.

Solutions to the shrinkage of the lake and desertification of the area are periodically proposed, but only the northern portion saw some improvement. What remains of the South Aral Sea is likely destined to disappear, leaving behind more desert and toxic dust storms. With no real solution in sight, people in the region will continue to be affected by health problems and, as fishing was their only source of income, they will keep living in poverty. While satellite images reveal how the once rich Aral Sea has now turned into a barren desert, the difficult living conditions of the people in the area are a much more painful reminder of how human activity can lead to vast ecological disasters and immense suffering.

Ships stranded in the desolate landscape of the area formerly occupied by the Aral Sea (Sebastian Kluger, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0).