Today the Arabic numerals (0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9) are the most widely used symbols for writing numbers, adopted by most countries around the world. These numbers derive from a system originally developed in India, and later introduced to Europe by Arabs starting in the 10th century. The Arabic numerals gradually spread to European countries, but only became commonly used in the 15th and 16th century, especially after the invention of the printing press. European colonialism and trade then popularized these numbers all over the world, replacing most other systems.

The Arabic numerals replaced the Roman numerals in Europe as the most widely used numbers, but during the Late Middle Ages various other systems were developed. Maybe the most peculiar of these is the system created by members of the Cistercian monastic order in the 13th century, now known as Cistercian numerals.

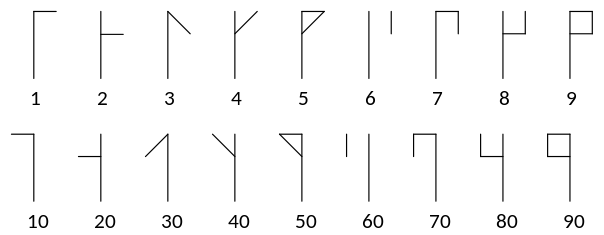

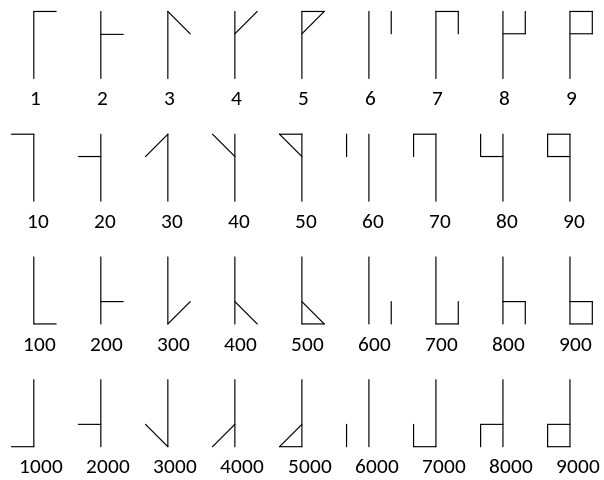

The system is based on the idea of using a single symbol able to represent any number from 1 to 9,999. Every digit has a horizontal or vertical line, with dashes added in different positions to indicate units, tens, hundreds, or thousands. In the vertical system, units are represented by adding strokes to the top right. The tens are formed by reversing the strokes added from right to left, and so they are located in the top left. Inverting the units creates the hundreds, located in the bottom right. Finally, the thousands are in the bottom left, made by reversing the hundreds. Combining these strokes together allows to represent all integers from 1 up to 9,999.

The vertical forms to represent units, tens, hundreds, and thousands in the Cistercian numerals (Meteoorkip, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0).

Slightly different forms could be found in different monasteries and across the centuries, and sometimes the strokes for some digits were swapped with each other. For example, 5 was written either as a dot or as a triangle (as in the image above), and the strokes for 3 and 4 were swapped with those for 7 and 8 in some manuscripts.

No stroke added to one of the corners means that the value for that power of ten is zero. The system has no symbol to represent the number zero, meaning that a single line with no strokes added was not defined as a possible numeral.

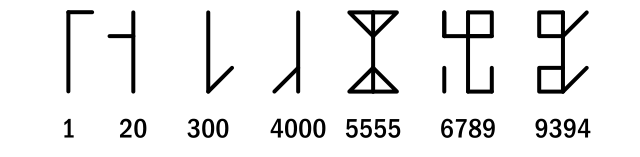

An example of the Cistercian numerals for the numbers 1, 20, 300, 4000, 5555, 6789, and 9394 (Tcr25, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0).

The same system works for the horizontal numbers, by rotating the symbol 90 degrees counter-clockwise, meaning that the units are in the top left, the tens in the bottom left, the hundreds in top right, and the thousands in the bottom right. The horizontal system was initially the most widely used, and the vertical one was only found in Northern France. However, the vertical numerals became more popular when revivals of the system were attempted between the 18th and 20th century.

The symbols were initially designed to only represent numbers between 1 and 9,999, but there were some later proposals to expand the system to higher numbers. In a few manuscripts, tens of thousands and millions were written by adding even more strokes to the symbol. Another proposal suggested to use the horizontal numerals for the smaller numbers, and the vertical numerals for higher powers of ten. This would allow the system to represent numbers up to 99,999,999. A 16th-century mathematician used this system, and rotated the symbols by 45 degrees to represent even higher numbers.

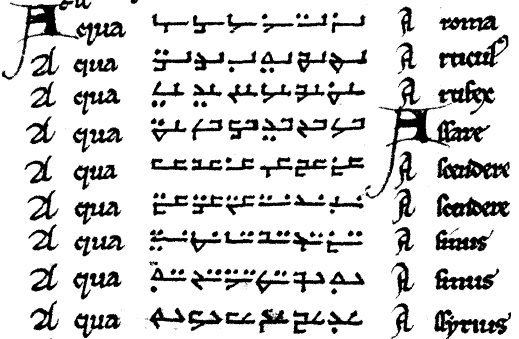

Horizontal Cistercian numerals in a 13th-century manuscript published in Belgium.

The Cistercian numerals can be found in a few manuscripts from all of Europe and dating between the 13th and 15th century. These numbers were used mainly to represent years, for page numbering, and in lists, but not for math or accounting.

The system saw a limited adoption outside the Cistercian order, and was described in a few treatises on arithmetic, but it was mostly abandoned by the 16th century. The Cistercian numerals remained in very limited use in Northern France and Belgium at least until the 18th century. Some attempts at reviving the system were made between the 18th and 20th century, with no success. The Cistercian numerals were described in the 2001 book The Ciphers of the Monks: A Forgotten Number-notation of the Middle Ages by British-American historian David A. King, which reintroduced the mostly forgotten system to a modern audience.