In 2006, the International Astronomical Union (IAU) introduced a new definition of planet, changing the way we classify the larger bodies in the Solar System. According to this definition, a planet is a celestial body that:

- orbits the Sun,

- is in hydrostatic equilibrium, meaning that it has a nearly round shape,

- it has “cleared the neighborhood” around its orbit.

While the first and second criteria are easy to understand, the third one needs a more in-depth explanation.

A celestial body that has “cleared the neighborhood” dominates the area around its orbit, and no objects of comparable size are located in the same zone, except for those under its gravitational influence, such as its satellites. During the latter stages of planet formation, the larger bodies gradually remove the smaller ones, causing them to either be destroyed, become satellites, be moved into a resonant orbit, or be ejected from their orbital zone. This is the process defined as “clearing the neighborhood”.

If a large body satisfies all three criteria, it is a planet. If an object that is not a satellite only satisfies the first two criteria and it has not cleared its neighborhood, it is regarded as a “dwarf planet”. An object that only satisfies the first requirement, and is not a satellite, it is classified as a “small Solar System body”.

This new definition of planet derived from a long-running dispute over the status of Pluto and other small objects in the Solar System. When Ceres was discovered in 1801, it was regarded as a planet, but as more and more bodies of comparable size were observed, it became clear that a new category of objects was needed. All the recently discovered bodies where then catalogued as “asteroids”.

In 1930, Pluto was discovered and was initially regarded as the ninth planet. By the 1990s, it was clear that Pluto was way smaller that any other planet, and with its eccentric and inclined orbit, many astronomers questioned its status as a planet. In the early 2000s various other bodies with sizes comparable to that of Pluto were discovered around the same orbit, and so the concept of dwarf planet was defined. So, which Solar System objects are classified as dwarf planets?

Image of Pluto taken by New Horizons in 2015 (NASA).

Pluto

Pluto is obviously the best known dwarf planet, and the prototype of this category of objects. Its mass is only around 0.2% of that of Earth and around 25 times smaller than the mass of the smallest planet, Mercury. Meanwhile its diameter is around half of that of Mercury and one-fifth of Earth’s diameter. The orbit of Pluto is eccentric, and ranges between 29.7 and 49.3 astronomical units (AU), with a semimajor axis of 39.5 AU. Because of this, Pluto is sometimes closer to the Sun than Neptune (whose orbit has a semimajor axis of 30 AU), but the inclination of Pluto’s orbit keeps the two bodies far away from each other. Pluto and Neptune are in a 2:3 orbital resonance, meaning that for every two orbits of Pluto around the Sun, Neptune makes three. While Pluto is the largest (but not the most massive) known trans-Neptunian object, various other bodies with comparable sizes and orbits have been discovered.

Pluto has five known satellites, the largest of which is Charon. As the diameter of Charon is over half that of Pluto, the two bodies are sometimes considered a binary system. The other four satellites, Styx, Nix, Kerberos, and Hydra, are much smaller. In 2015, the New Horizons spacecraft became the first to visit Pluto and its system. Thanks to this mission, astronomers were able to observe that Pluto has a tenuous atmosphere and a varied surface with different geographical and geological features.

Ceres

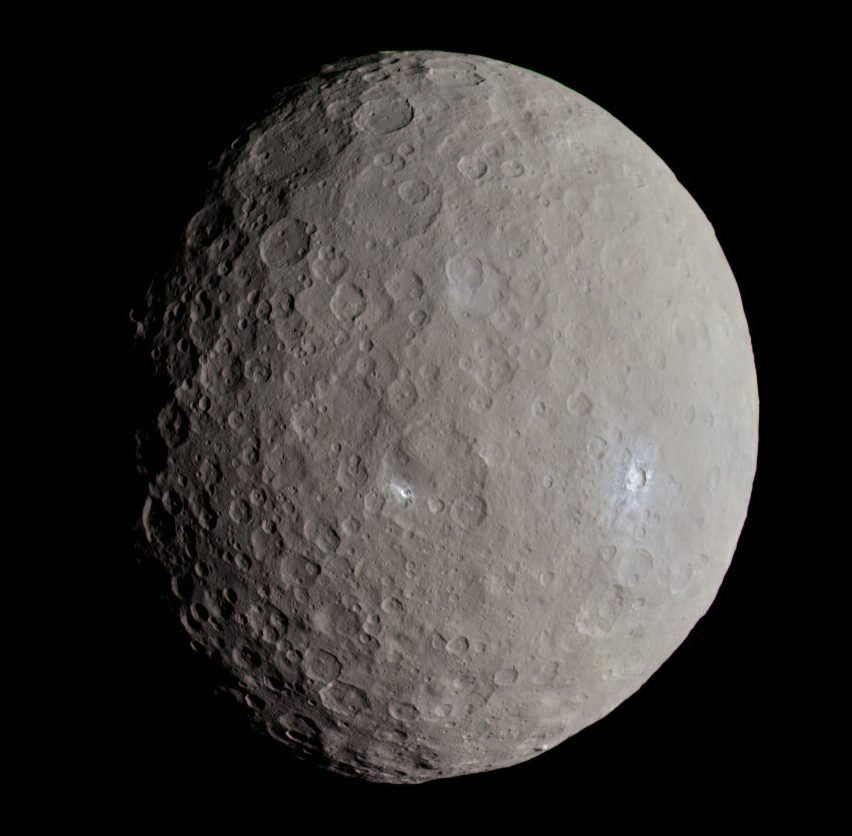

As mentioned above, Ceres was the first asteroid ever discovered and, similarly to Pluto, it was initially regarded as a planet. It is located among the main asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter and its orbit has a semimajor axis of 2.8 AU. Ceres is the largest object in the asteroid belt, but it is less than half the size of Pluto and around 7% of its mass. In 2015, the spacecraft Dawn reached Ceres and studied its surface, discovering evidence of cryovolcanism. The mission ended in 2018, but Dawn remains in orbit around Ceres.

Image of Ceres taken by Dawn in 2015 (Justin Cowart).

Eris

Eris is the most massive dwarf planet and known trans-Neptunian object in the Solar System, located in the scattered disc. However, its diameter is slightly smaller than Pluto’s. Discovered in 2005, it was immediately clear that it was quite massive, and it was initially described as the “tenth planet”. The discovery of Eris, and the prospect of finding other similar objects, led the IAU to define the concept of dwarf planet. Eris has a moon, called Dysnomia, which is about one-fourth the size of Eris and also the second-largest satellite of a trans-Neptunian object, after Charon. The orbit of Eris is even more inclined and eccentric than that of Pluto, and extends between 38 AU and 97 AU, with a semimajor axis of almost 68 AU.

Haumea

Haumea is a trans-Neptunian object discovered in 2004. It is about one-third the mass of Pluto, with an eccentric and inclined orbit ranging between 29 AU and 49 AU, and a semimajor axis of 43 AU. Haumea is believed to rotate so quickly that its shape has been distorted into an ellipsoid, while keeping hydrostatic equilibrium. Estimates on the dimensions of the ellipsoid vary, with the mean diameter being around two-thirds of Pluto’s. Haumea has two moons, Hiʻiaka and Namaka, and in 2017 a ring system was discovered around the dwarf planet, the first ever observed for a trans-Neptunian object.

Makemake

Makemake is another trans-Neptunian object, located in the Kuiper belt and discovered in 2005. Similarly to the other dwarf planets in the same region, its orbit is inclined and eccentric, with a semimajor axis of 45 AU. The diameter of Makemake is about 60% of that of Pluto, while its mass is just one-fourth of Pluto’s, so it is somewhat smaller than Haumea. Makemake has one known satellite, which still does not have a permanent name and is provisionally nicknamed MK2.

Images of Eris, Haumea, and Makemake taken by the Hubble Space Telescope (NASA, ESA, and M. Brown, NASA, NASA, ESA, and A. Parker and M. Buie (Southwest Research Institute)).

Other possible dwarf planets

In addition to Pluto, Ceres, Eris, Haumea and Makemake, the objects commonly regarded as dwarf planets are Gonggong, Quaoar, Sedna, and Orcus, and sometimes Salacia. The largest of these is Gonggong, which is about half the size of Pluto and has one satellite, Xiangliu. Slightly smaller than Gonggong is Quaoar. In addition to a moon named Weywot, Quaoar also has a ring system. Orcus is slightly smaller than Ceres and, like Pluto, it has a 2:3 orbital resonance with Neptune and a large moon, called Vanth. Meanwhile Salacia is considered a borderline case and there is less consensus about its classification as a dwarf planet. Salacia is about one-third the size of Pluto and it has a moon, Actaea.

Sedna is one of the most peculiar trans-Neptunian objects and possible dwarf planets. Discovered in 2003, it is a bit larger than Ceres and has one of the wider and more elongated orbits of any known Solar System body. Its aphelion (the farthest distance from the Sun) is a whopping 937 AU, while its perihelion (closest approach to the Sun) is 76 AU, two and a half times the distance of Neptune from the Sun. Various other objects with quite similar orbits are now known, and this clustering prompted some astronomers to propose the presence of a still-undiscovered large planet located in the farthest reaches of the Solar System, whose gravitational influence might explain this anomaly.

There are numerous other bodies that might be classified as dwarf planets. Among these are some trans-Neptunian objects smaller than Salacia, such as 2002 MS4, 2002 AW197, Varda, 2013 FY27, Ixion, and 2003 AZ84. Smaller objects are unlikely to be dwarf planets. Also, there are various other distant objects whose sizes are still unknown, and are thus hard to classify.

Comparison of the largest known trans-Neptunian objects along with Earth and the Moon (Lexicon, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0). If included, Ceres would be between Sedna and Orcus.

| Name | Mean diameter (km) | Mass/Mass of Pluto | Semimajor axis (perihelion-aphelion) (AU) | Orbital eccentricity | Orbital inclination (to the ecliptic) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Earth (for comparison) | 12742 | 458.34 | 1.00 (0.98-1.02) | 0.02 | 0.0° |

| Mercury (for comparison) | 4879 ±2 | 25.33 | 0.39 (0.31-0.47) | 0.20 | 7.0° |

| Moon (for comparison) | 3475 | 5.63 | – | 0.05 | 5.1° |

| Pluto | 2377 ±2 | 1.00 | 39.5 (29.7-49.3) | 0.25 | 17.2° |

| Eris | 2326 ±12 | 1.25 | 67.9 (38.3-97.5) | 0.44 | 44.0° |

| Haumea | ≈1560 | 0.31 | 43.1 (34.6-51.6) | 0.20 | 28.2° |

| Makemake | 1430 +38-22 | 0.24 | 45.4 (38.1-52.8) | 0.16 | 29.0° |

| Gonggong | 1230 ±50 | 0.13 | 67.5 (33.8-101.2) | 0.50 | 30.6° |

| Quaoar | 1086 ±4 | 0.09 | 43.7 (41.9-45.5) | 0.04 | 8.0° |

| Sedna | 995 ±80 | Unknown | 506 (76-937) | 0.85 | 11.9° |

| Ceres | 939 | 0.07 | 2.77 (2.55-2.98) | 0.08 | 10.6° |

| Orcus | 910 +50-40 | 0.04 | 39.2 (30.3-48.1) | 0.22 | 20.6° |

| Salacia | 846 ±21 | 0.04 | 42.2 (37.7-46.7) | 0.11 | 23.9° |

| 2002 MS4 | 796 ±24 | Unknown | 41.7 (35.7-47.8) | 0.14 | 17.7° |

| 2002 AW197 | 768 ±39 | Unknown | 47.0 (40.9-53.2) | 0.13 | 24.4° |

| 2013 FY27 | 742 +78-83 | Unknown | 58.6 (35.2-81.9) | 0.40 | 33.3° |

| Varda | 740 ±14 | 0.02 | 46.1 (39.5-52.7) | 0.14 | 21.5° |

| 2003 AZ84 | 727 +62-66 | ≈0.01 | 39.4 (32.2-46.6) | 0.18 | 13.6° |

| Ixion | 710 ±1 | Unknown | 39.8 (30.0-49.6) | 0.25 | 19.6° |

| 2021 DR15 | ≈700 | Unknown | 67.2 (37.8-96.5) | 0.44 | 30.7° |

| 2004 GV9 | 680 ±34 | Unknown | 42.2 (38.7-45.6) | 0.08 | 22.0° |

| 2005 RN43 | 679 +55-73 | Unknown | 41.4 (40.6-42.1) | 0.02 | 19.3° |

| 2015 KH162 | ≈671 | Unknown | 61.8 (41.5-82.1) | 0.33 | 28.9° |

| 2002 UX25 | 659 ±38 | 0.01 | 42.5 (36.5-48.5) | 0.14 | 19.5° |

| 2018 VG18 | ≈656 | Unknown | 81.7 (38.3-125.0) | 0.53 | 24.3° |

| Varuna | 654 +154 -102 | Unknown | 42.7 (40.3-45.1) | 0.06 | 17.2° |

| 2005 RM43 | ≈644 | Unknown | 89.6 (35.1-144.1) | 0.61 | 28.8° |

| Gǃkúnǁʼhòmdímà | 642 ±28 | 0.01 | 72.8 (37.5-108.1) | 0.48 | 23.4° |

| 2010 RF43 | ≈636 | Unknown | 49.7 (37.5-61.9) | 0.25 | 30.6° |

| 2014 UZ224 | 635 +65-72 | Unknown | 107.6 (38.3-177.0) | 0.64 | 26.8° |

| 2014 EZ51 | ≈626 | Unknown | 52.4 (40.4-64.4) | 0.23 | 10.3° |

| 2015 RR245 | ≈626 | Unknown | 81.4 (33.9-128.8) | 0.58 | 7.6° |

| Chaos | 600 +140 -130 | Unknown | 45.8 (41.0-50.6) | 0.11 | 12.0° |

Comparison of the physical and orbital characteristics of confirmed and possible dwarf planets with mean diameters larger than 600 km, along with Earth, Mercury, and the Moon. Various other objects might have similar sizes but are still not well known. The semi-major axis of the orbit of the Moon has been omitted since it is Earth’s satellite.