Mars is the fourth planet from the Sun in our Solar System, and it is one of the most studied celestial bodies. Observed since ancient times, it was the target of some of the earliest space exploration missions in the 1960s, and it has been reached by several uncrewed spacecrafts ever since. Today, thanks to these missions, we have a deep understanding of Mars’ fascinating geology and geological history, but before diving into this 4.5-billion-year-long history, we need to introduce some characteristics of the Red Planet.

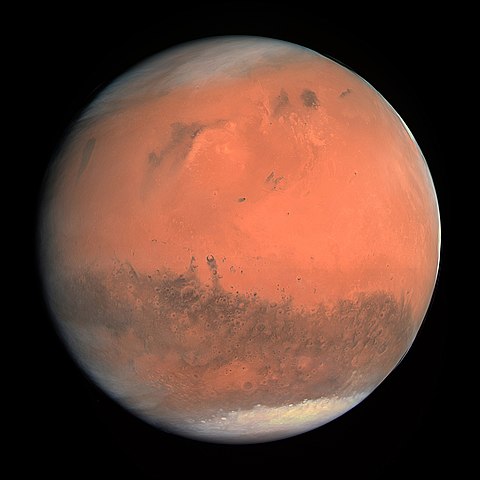

True color image of Mars taken by the ESA spacecraft Rosetta in 2007 (ESA & MPS for OSIRIS Team MPS/UPD/LAM/IAA/RSSD/INTA/UPM/DASP/IDA, CC BY-SA IGO 3.0).

Mars shares many similarities with Earth, despite being just slightly over half the size of our planet in terms of radius and about one tenth in terms of mass. A day on Mars is just 37 minutes longer than one on Earth and, thanks to a similar axial tilt, both planets experience the change of seasons. Temperatures on Mars can vary widely, from -143°C at the poles during winter to 35°C at the equator during summer, but a huge difference with Earth regards its atmosphere. The atmosphere of Mars is very rarefied, with a pressure of only 0.006 times the pressure of Earth’s atmosphere, and it is composed of about 95% carbon dioxide, which makes it unbreathable and toxic for humans.

The internal structure of Mars is also similar to the our planet’s, with a core, a mantle, and a crust. Unlike Earth, Mars’ mantle is believed to be inactive and this is reflected in the lack of a strong magnetic field surrounding the planet. The crust is mainly basaltic, revealing its volcanic origin, and while there is no liquid water on Mars’ surface today, numerous geological features such as channels and deltas hint at a past presence of large oceans and rivers.

Many geographic elements can also stimulate our curiosity on the planet’s history, as the largely flat northern hemisphere contrasts with the highly cratered and rugged southern hemisphere, wide volcanic plateaus rise above the land, and long canyons run through the surface. To understand the origin of all these features and characteristics we now need to explore the geological history of Mars, with the disclaimers that the dates are approximate and subject to huge error bars of hundreds of millions of years, and that there is still much that remains unknown.

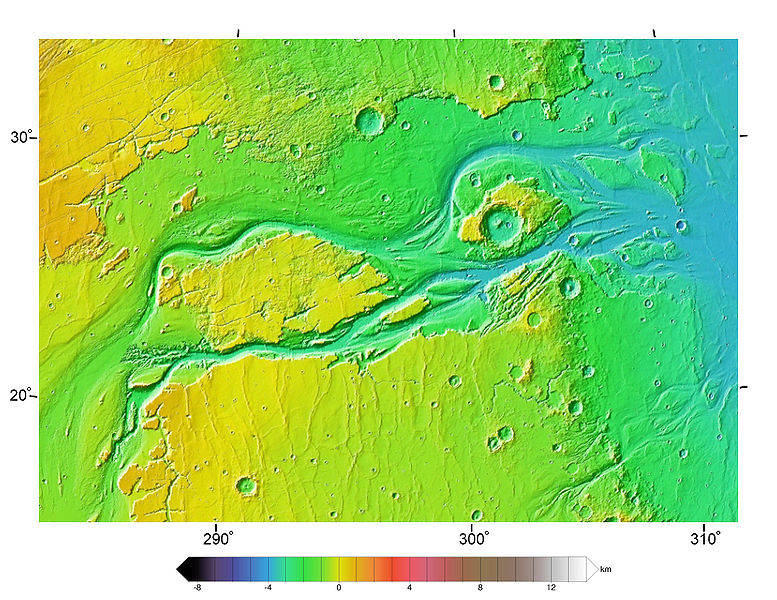

Topographic map of Mars by the Mars Orbiter Laser Altimeter (MOLA) on the NASA spacecraft Mars Global Surveyor. The lowest elevations are in blue and purple, while the highest ones are in brown and white. There is a clear difference between the lowlands of the northern hemisphere and the more rugged southern one. The large region on the west is Tharsis, while the wide impact crater in the southeast is the Hellas Basin.

Similarly to the other rocky planets, Mars was formed from the accretion of material in the protoplanetary disk orbiting the Sun around 4.5 billion years ago. The first epoch of Mars’ history stretches from the planet’s formation until 4.1 billion years ago. This period is called Pre-Noachian, and not much from this far back in time has survived until today, as following events likely erased many of the features from this epoch. Nonetheless, it is believed that the crustal dichotomy between the northern and southern hemisphere originated during this time, maybe as a result of the impact of a large protoplanet.

The Noachian period dates from 4.1 to 3.7 billion years ago, roughly corresponding with the age of the Late Heavy Bombardment, an era during which a huge number of asteroids impacted with the rocky planets of the internal Solar System, an event likely caused by the instability and migration of the giant planets of the outer Solar System. Indeed, there is a large number of craters on the Martian surface dating back to this period, like those in the Noachis Terra, a landmass that formed during this time and gives the name to the whole epoch.

During the Noachian, Mars was very geologically active, with extensive volcanism taking place especially in the Tharsis region, where the accumulation of enormous quantities of volcanic material continued into the following geological period. Due to the volcanic activity and the heat generated by the many impact events, the atmosphere of Mars in the Noachian may have been much more denser, leading to a warm and wet climate, with precipitation of liquid water that eventually led to the formation of lakes, rivers, and even a huge ocean in the northern basin.

Another sea may have been located in the southern Hellas basin, a wide impact crater formed during the Late Heavy Bombardment. Around 4 billion years ago Mars had cooled enough after its formation that the internal activity ceased, and due to the absence of convection in the mantle, the magnetic field generated by these movements slowly faded, with the solar wind then wiping out what remained of it. Without the protection of its magnetic field, the solar wind could directly hit the Martian atmosphere, removing more and more of it.

After the end of the Late Heavy Bombardment, Mars entered the Hesperian period, ranging from 3.7 to 3 billion years ago. Volcanism continued and was widespread during this epoch, with many lava plains dating back to this time, such as the Hesperia Planum in the southern highlands. By this time, the huge shield volcanoes of the Tharsis region, that are still the largest in the Solar System, had formed, and so much volcanic material had accumulated in this area that its huge weight cracked the crust of Mars producing fractures, ridges, and the large canyon system of the Valles Marineris.

During the Hesperian, the Martian climate began to shift from warm and wet to cold and dry, with its atmosphere reaching its current density at the end of this period. Water was frozen, but volcanic and tectonic activity could crack the icy layer causing the underlying liquid water to overflow and leading to catastrophic floods. The flow of water excavated channels directed towards the lower areas, where sediments piled up.

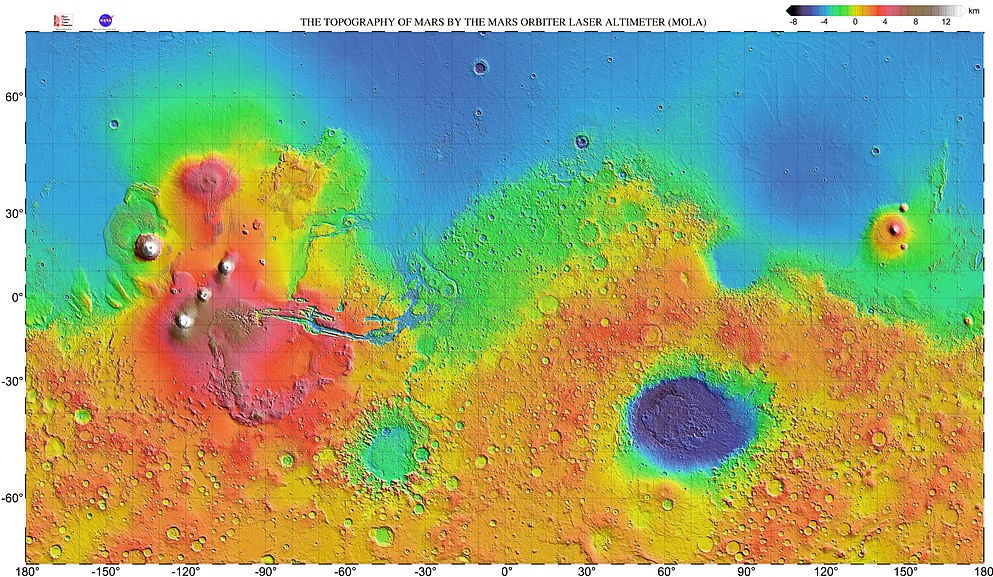

Topographic map of the Kasei Valles, one of the largest outflow channel systems on Mars, as seen by the Mars Orbiter Laser Altimeter (MOLA) on the NASA spacecraft Mars Global Surveyor (Areong, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0).

The longest and current period of Mars’ history is the Amazonian, starting around 3 billion years ago and continuing to the present day. The climate of the planet finally became cold and arid, with liquid water disappearing from the surface. Geologic activity became rare and sporadic, while the number of impacts on the surface has been very low in this period, as shown by the few craters and features of younger terrains such as the Amazonis Planitia. The most important activities during the Amazonian are due to the presence of ice, that accumulated at the poles forming the polar caps we see today. Occasional ice melting with small releases of liquid water can be still seen on the Martian surface, but otherwise any kind of activity is now very rare.

A lot is still to be discovered about the history of Mars, the uncertainties are huge and the obscure points are plenty, as many questions remain unanswered. What did the ancient, water-rich, Mars look like? Could it have harbored life? And if so, what kind of life? Future exploration missions will hopefully find out. From a water-rich and volcanically active planet to an arid and inactive one, the fascinating past of Mars can teach us a lot about its present while we wait for its future, maybe one in which humans set foot on the Red Planet for the first time.