Deep among the hills of Southern Africa, in the modern country of Zimbabwe, lie the ruins of Great Zimbabwe, the capital of what was once the richest kingdom of this part of the world. This is known as the Kingdom of Zimbabwe, and from the 13th to the 15th century it ruled over a large area, dominating the trade between the interior of Africa and the southeastern coast of the continent.

Position of Great Zimbabwe in Zimbabwe, near the city of Masvingo (edited from a work by EC-JRC (ECHO), Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0).

This area had been inhabited by Bantu farmers for centuries, and from around the 10th century some small states emerged in the Zimbabwean plateau. These kingdoms were inhabited by the Shona people, a Bantu ethnic group that to this day forms the majority of the population of Zimbabwe. At the same time, Arab merchants began to visit the coast of Southeastern Africa along the Indian Ocean, in modern-day Mozambique.

At the end of the 11th century, the Kingdom of Mapungubwe developed in the area between the borders of what today are Zimbabwe, South Africa, Botswana, and Mozambique, along the Limpopo river. Mapungubwe is regarded by archaeologists as the first class-based society in Southern Africa, with a clear separation between the leaders and other inhabitants. Their economy was mainly based on farming, but they also controlled the trade of gold and ivory between the interior of Africa and the Arab merchants on the coast.

North of Mapungubwe, another society started to emerge. Ancestors of the modern Shona people began to erect large stone structures around the 11th century, founding the town of Great Zimbabwe. The name “zimbabwe” itself means “great house of stone” in the Shona language, and was used to refer to many settlements in this area. Among the around 200 known “zimbabwes”, the largest and most powerful was given the name Great Zimbabwe by Western scholars, to distinguish it from other smaller ruins.

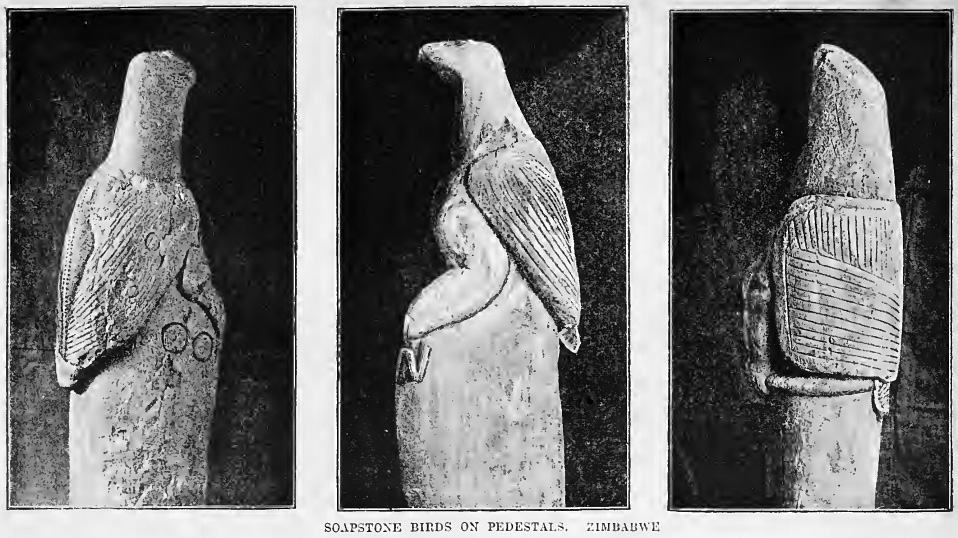

The archaeological site is the largest group of ancient stone structures in Sub-Saharan Africa, and it is divided into three areas, the Hill Complex, the Valley Complex and the Great Enclosure. The oldest area is the Hill Complex, a group of structures located on top of a rocky hill, where once stood the sculptures of the Zimbabwe Bird. These statues were sacred symbols for the Shona people, and were only found here. The Zimbabwe Bird is now used as the national emblem of Zimbabwe, and even appears on the country’s flag. Taken away by European explorers in the 19th century, some of the sculptures have now been returned to the country.

The Zimbabwe Bird statues in a picture from the late 19th century.

The most imposing structure in Great Zimbabwe is known as the Great Enclosure. This was probably the royal palace or residence of the local rulers, and features a tall conical tower and a series of walls. The center of power in the kingdom likely moved from the Hill Complex to the Great Enclosure in the 12th century. The Valley Complex instead is a group of stone ruins with different periods of occupation.

Numerous ancient artefacts were found in the ruins, including stone figurines, pottery, worked ivory, and objects made of iron, copper, bronze, and gold. Various foreign artefacts were also found here, such as glass and porcelain from Persia and China, and coins from Arabia, attesting the international trade links that made this kingdom rich. Great Zimbabwe mainly traded iron and gold with foreign merchants, but also controlled the local agricultural trade and the commerce of cattle in a large area of Southern Africa.

Great Zimbabwe from above, with the Hill Complex in the lower left and the Great Enclosure in the upper right (Janice Bell, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0).

Great Zimbabwe eclipsed Mapungubwe in the early 13th century, and became the most powerful center in the region. In the end, Mapungubwe was abandoned in favor of Great Zimbabwe. At its peak, the town had a population of around 10,000 people, and was the capital of the so-called Kingdom of Zimbabwe. However, according to the legend, around the year 1430 a prince called Nyatsimba Mutota traveled north, maybe in search of new sources of salt, or after a dispute over control of the kingdom. After defeating the local rulers, he founded the Kingdom of Mutapa in what is now northern Zimbabwe.

The new kingdom quickly gained power, as other states voluntarily joined Mutapa. Around 1450, Mutapa was already the most powerful state in the region, and Great Zimbabwe was abandoned. Mutapa continued to expand, and in a few decades it came to rule over a large area between the Indian Ocean and the deep interior of Africa. Instead, the smaller Kingdom of Butua emerged in the southern region once ruled by Great Zimbabwe.

Portuguese merchants arrived on the southeastern coast of Africa in the early 16th century, and quickly began to dominate commerce in the region. Some Portuguese explorers traveled to Great Zimbabwe during this time and described the site, which appeared to be still inhabited. The ruins were rediscovered in 1867 by German explorers and were visited by various Western archaeologists over the following decades.

European explorers initially did not believe that Africans were capable of building such large structures, and came up with all kind of theories to justify a Phoenician, Roman, or Arab origin of the site. Despite this, by the 1950s the consensus among experts was that the structures were erected by the ancestors of the modern Shona people, but the white government of Rhodesia denied that the site was built by indigenous Africans. The colonial government held the position that the structures were erected by non-blacks, and for decades pressured archaeologists to hide the truth, censoring books, documentaries, and newspapers that talked about the indigenous origins of the site. The ruins of Great Zimbabwe thus became a symbol of national pride for the local black population, and when in 1980 the country finally gained its full independence they chose the name Zimbabwe, in honor of the ancient civilization. In 1986, Great Zimbabwe was recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage site.