All over the world, April 1 is a day in which pranks and hoaxes are common, a custom known as April Fools’ Day. While this celebration only originated in modern times in the Western world, similar customs can be found since ancient times, mostly in Europe.

Maybe the oldest instance of a similar tradition is the Roman Hilaria. This was a religious festival observed around the time of the spring equinox, at the end of March. The Hilaria was dedicated to the goddess Cybele and her consort Attis, who died and resurrected. The Romans adapted this feast from an earlier Greek celebration, while the myth originated in Anatolia, to represent the rebirth of nature in spring after the cold winter months.

The Roman festival included various traditions that spanned the second half of March, but the Hilaria proper was observed on March 25, when the resurrection of Attis was celebrated. As such, March 25 was a “day of joy”, and people were allowed to play all kind of games. A popular tradition was to dress up in disguises and imitate others, even magistrates.

Another festival that included jokes and disguises was the Feast of Fools, observed by the clergy in Europe during the Middle Ages. During this feast, the participants parodied the ecclesiastical rituals and elected a fake bishop or even a fake pope, reversing the roles of higher and lower members of the clergy. The festival lasted a whole week, starting on December 26 and culminating on January 1. This feast originated in Southern France around the 12th century and later expanded to all of Europe. Often criticized by Catholic writers, the festival was forbidden by the Council of Basel in 1431. Despite this, limited instances of the festival survived until the 18th century. The traditions of the Feast of Fools and the Roman Hilaria not only influenced April Fools’ Day, but also other festivals such as Carnival, Mardi Gras, and Halloween.

A 14th-century miniature representing a scene of the Feast of Fools.

The exact origins of April Fools’ Day are not known, and several theories have been proposed. According to some historians, the festival might be linked to New Years’ Day, which was celebrated on March 25 in many European countries during the Middle Ages, with the holidays lasting a week, until April 1. In the mid 16th century various countries started moving New Years’ Day to January 1, which was adopted as the start of the year in most of Europe over the following decades. Those who celebrated New Years’ Day on January 1 made fun of those who celebrated on April 1, calling them “April fools”. Also, since it was a tradition to exchange gifts on New Years’ Day, when the celebration was moved to January 1, some people jokingly gave empty boxes on April 1 to symbolize the now-obsolete tradition.

The first mention of a poisson d’avril (literally “April’s fish”, the name of the festival in French) was in 1508. However, more than a festival, this could actually be a reference to the fact that since fish were plentiful and easier to catch in spring, the April fish were more gullible than fish in other seasons. The first unambiguous reference to April Fools’ Day instead comes from a 1561 poem describing a nobleman who sent his servant on foolish errands on April 1.

A ticket to the “annual ceremony of washing the lions” at the Tower of London, from 1857.

The tradition of pulling pranks on April 1 spread to all of Europe in the 17th and 18th century. A notable prank happened in London in 1698, when many people were tricked into going to the Tower of London to “see the lions washed”, an event that obviously did not take place. The same prank was occasionally repeated throughout the 18th and 19th century.

In Italy and French-speaking countries, where April Fools’ Day is known as pesce d’aprile and poisson d’avril (“April’s fish”), the festival has included references to fish since the 19th century, and the prank of attaching a paper fish to a person’s back became really popular. In Spain, Hispanic America, and the Philippines, December 28 is another day for pranks, coinciding with the Christian celebration of the Day of the Holy Innocents.

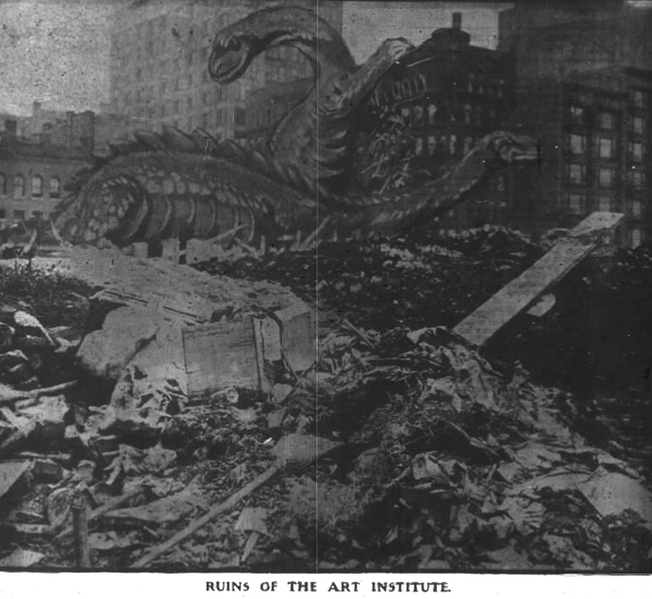

Dinosaurs among the ruins of Chicago as depicted in a hoax by the Chicago Tribune in 1906 (Artful Dodger, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0).

With the spread of newspapers, radio, and television, many news outlets started publishing fake and often absurd stories on April Fools’ Day, a tradition that only grew more popular with the Internet. Now it is common for many websites to pull some kind of prank on April 1, and the tradition is observed all over the world. Here are just a few of the most famous hoaxes published on April Fools’ Day:

- In 1905 the German newspaper Berliner Tageblatt reported that thieves had stolen all the gold and silver in the U.S. Federal Treasury. The hoax was picked up by many newspapers in Europe, who believed it was a true story.

- In 1906 the Chicago Tribune published an elaborate article describing hordes of dinosaurs invading Chicago, illustrated with doctored photographs.

- In 1957 the BBC reported that people in Switzerland harvested spaghetti from a “spaghetti tree”, which resulted in hundreds of calls by people asking how they could grow their own spaghetti trees. This was later described by CNN as “the biggest hoax that any reputable news establishment ever pulled”.

- In 1962 the Swedish national television described how people could get color TV by placing nylon on the screen, and thousands tried it.

- In 1965 the BBC described a new technology, called “smellovision”, that allowed viewers to smell the scents coming from the television studio. They demonstrated this by chopping onions and brewing coffee, and many viewers called to confirm that they were able to smell the aromas.

- In 1969 a Dutch broadcaster reported that inspectors with remote scanners would search for people who did not pay their radio and TV taxes, and the only way to avoid being caught was to wrap the devices with aluminium foil. The next day most supermarkets were sold out of aluminium foil, and thousands suddenly paid their taxes.

- In 1976 British astronomer Patrick Moore described on BBC Radio 2 the “Jovian–Plutonian gravitational effect”, an alignment of the two celestial objects that would result in people being lighter at exactly 9:47 am, and invited people to jump. Several listeners called to confirm that they could almost float in the air.

- In 1977 British newspaper The Guardian published a seven-page supplement describing the fictional country of San Serriffe, located in the middle of the Indian Ocean. Many people called airlines and travel agents to ask how they could visit the country.

- In 1980 Boston television station WNAC-TV reported that a volcano had erupted in Milton, Massachusetts. This resulted in many residents fleeing the town and the executive producer of the news broadcast being fired.

- In 1993 a radio station in San Diego, California, announced that the Space Shuttle would land on a small local airport, and over a thousand people drove there to see it, just to find the airport empty.

- In 2008 the BBC aired an elaborate segment describing the discovery of a colony of flying penguins in Antarctica, and followed their flight to the Amazon rainforest.

- In 2013 a newspaper in Puerto Rico published an article announcing that the Royal Spanish Academy decided to remove the letter ñ from the Spanish alphabet, replacing it with nn. The news was taken seriously by many, and the Academy had to repetedly deny the allegation.