A legendary figure in European history, Attila was one of the most feared enemies of the Romans and, during his prime, he ranked among the most powerful sovereigns in the world. Attila was the King of the Huns when they were at the peak of their strength, ruling over a territory that extended from the Caspian Sea to the Rhine, and from the Baltic Sea to the Danube, uniting most of the Barbarian tribes of the region under his rule.

After leading many devastating raids against the Romans and sacking numerous cities, he gained the nickname Flagellum Dei (“Scourge of God”). Attila was said to be so ferocious that no grass would grow wherever he passed through, and there are many accounts of bloody massacres ordered by him.

Despite the many legends surrounding his name, not much is actually known about Attila, and almost all contemporary accounts were written by his enemies. The only known physical description of Attila is provided by Eastern Roman bureaucrat Jordanes, who cites an account by Greek historian Priscus, who met the King of the Huns as a diplomat. Priscus depicts Attila as following: “Short of stature, with a broad chest and a large head; his eyes were small, his beard thin and sprinkled with grey; and he had a flat nose and swarthy skin, showing evidence of his origin.”

According to some historians, this description suggests that Attila was of East Asian or Central Asian descent. This topic opens a wider debate about the Huns in general, as their origin is still unclear and little is known about their early history.

Depiction of Attila in the Chronicon Pictum, a Hungarian illustrated chronicle from the 14th century.

The Huns before Attila

The Huns were a nomadic people who lived in the Eurasian steppe between Central Asia and Eastern Europe. It is unknown where the Huns originally came from, and links with various other peoples, most notably the Xiongnu tribes of the Mongolian Plateau, have been proposed, but there is no consensus among historians on this matter. Also, only a few words of the Hunnic language are known, mostly proper names cited in Greek and Latin sources. Thus, the language remains unclassified.

Anyhow, the Huns appear in Western history in the late 4th century, when they defeated the Alans and the Goths in the steppe between the Caspian Sea and the Black Sea, forcing thousands to flee and seek refuge inside the Roman Empire. The Hunnic invasions triggered a series of migrations that led many Barbarian peoples to move west, entering Roman territory and causing much trouble to the Empire.

Over the next few decades, the Huns pillaged various cities in the Balkans, the Caucasus, and the Middle East. In 395, the Huns invaded the Sasanian Empire, marching into Persia but ultimately failing to take the Sasanian capital Ctesiphon. During the early 5th century, the Huns launched various raids into Roman territory, but they always returned north of the Danube.

Early life and rise of Attila

Attila was born during this time, as the son of a chieftain named Mundzuk, brother of the Hunnic rulers Octar and Rugila. His birthdate is unknown, with the most commonly proposed dates being 395 and 406. Almost nothing is known about his childhood but, as was the custom among the Huns, he and his brother Bleda probably learned archery, sword fighting, and horse riding at an early age.

Rugila died in 434, and Attila and Bleda became co-rulers of the Hunnic Empire. The following year, the two kings signed a treaty with the Eastern Roman Empire, forcing them to double the yearly tribute they already paid to the Huns.

After a failed attack against the Sasanian Empire, the Huns again turned their attention to Europe, crossing the Danube and attacking various Roman cities in the Balkans. Meanwhile, the Romans were dealing with the Vandals, which were invading Northern Africa, and many troops were diverted to this region, leaving the Balkans undefended against the Hunnic attacks. The Huns advanced all the way to Constantinople, and the Romans had to negotiate a peace treaty. The yearly tribute to the Huns was tripled, and the invaders retreated back to their territory. Bleda died around this time (probably in the year 445), and Attila became the sole ruler or the Huns. Some sources suggest that Bleda was killed by Attila, but his actual cause of death is unclear.

Over the next few years, the Huns faced some internal struggles, with one tribe rebelling against Attila. The uprising was eventually defeated, but the Eastern Roman Empire took advantage of the situation to stop paying tributes to the Huns. Attila responded with another invasion of the Balkans, reaching Constantinople and again forcing the Romans to raise their yearly tribute to the Huns.

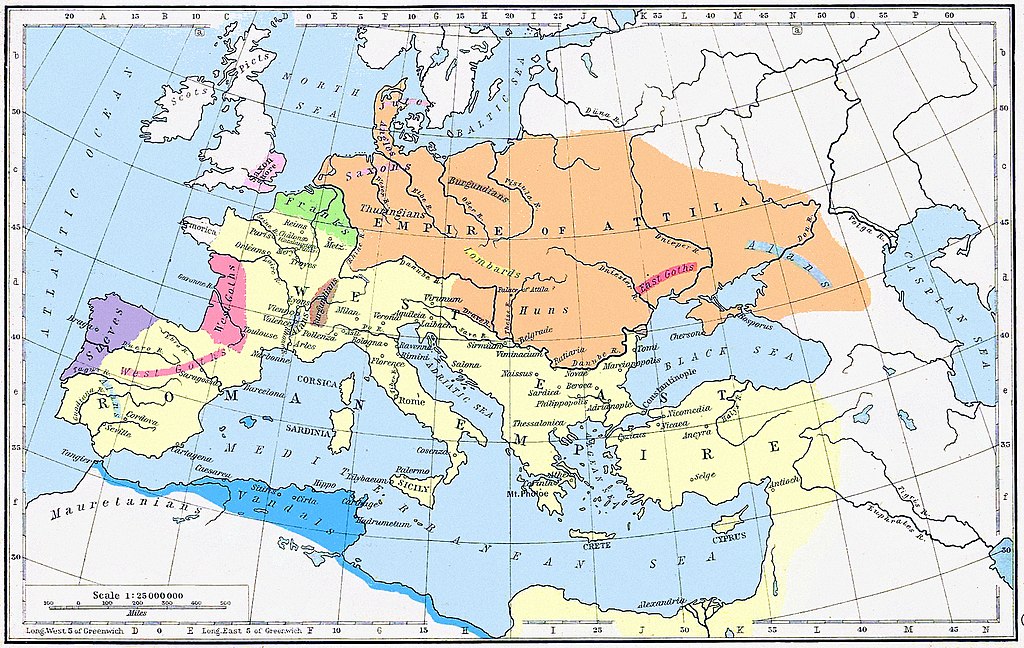

Map of the Hunnic Empire under the rule of Attila around the year 450.

Wars against the Western Roman Empire

In 450, Attila finally turned his attention to the west. The Huns had good relations with the Western Roman Empire until this point, especially with the Roman general Aetius, and they even allied against the Visigoths. However, Honoria, sister of the Western Roman emperor Valentinian III, sent her engagement ring to Attila asking for help to escape her forced betrothal to a Roman senator. Attila interpreted the message as a marriage proposal, which he accepted, claiming half of the Western Roman Empire as dowry.

Meanwhile, the death of a Frankish ruler led to a succession struggle among the Franks in eastern Gaul. Attila interfered in the matter, invading Gaul in 451 and devastating many cities in the region. The Romans and the Visigoths formed an alliance against Attila, clashing with the Huns in the Battle of the Catalaunian Plains in north-eastern France. The clash ended with a strategic victory of the Roman-Visigoth alliance, although Visigoth king Theodoric died in battle.

After retreating from Gaul, Attila renewed his claim to Honoria and the territory of the Western Roman Empire, and launched an invasion of Italy in 452. The Huns crossed the Alps and laid siege to the prosperous Aquileia, which was the main center in the area, and razed it to the ground. The Huns devastated the countryside of Veneto, sacking many cities and destroying the town of Altinum, forcing many to flee to the islands of the Venetian Lagoon. The refugees settled here, eventually leading to the rise of Venice.

The Huns sacked many cities in Northern Italy, such as Padua, Vicenza, Verona, Brescia, Bergamo, Mantua, and Milan. As his army was probably hindered by disease and starvation, Attila halted his advance at the Po river. The King of the Huns met some Roman envoys, including Pope Leo I, near Mantua, and negotiated a peace. The Hunnic king was under pressure to retreat from Italy, both because the region suffered a famine the previous year, and there were not enough supplies to support the invasion, but also because the Eastern Roman Empire, which had stopped paying tributes, was attacking the Huns on the Danube.

The Meeting of Leo the Great and Attila, a fresco painted between 1513 and 1514 by Raphael inside the Apostolic Palace in the Vatican.

Attila died suddenly in early 453. According to contemporary reports, he was celebrating his latest marriage when he started bleeding and died of hemorrhage. It has been suggested that years of excessive alcohol consumption might have led to a weakening of his esophageal varices, which eventually ruptured, leading to internal bleeding and the death of the King of the Huns.

A large funeral was held, and Attila was reportedly buried with many riches in a secret place. Those who buried the king were killed in order to keep the location of the tomb hidden. To this day, the burial site has never been found.

Decline of the the Huns and the legacy of Attila

After the death of Attila, the Hunnic Empire was ruled by his sons Ellac, Dengizich, and Ernak. A Germanic coalition revolted against the Huns and defeated them in the Battle of Nedao in 454. After this defeat, the Huns slowly lost control over their subjects and their territory. In 467, Dengizich launched an attack against the Eastern Roman Empire, but he was defeated and killed two years later in Thrace. The kingdom of the Huns effectively ended here, and they were absorbed into other tribes.

Attila became a legendary figure over the following centuries, and many tales and poems were written about him. He notably appears, with the name Etzel, as one of the main characters in The Song of the Nibelungs, a Germanic epic poem written in the 13th century. Another legend claims that the members of the Árpád dynasty, that ruled Hungary between the 9th and 14th century, were the descendants of Attila. To this day, the King of the Huns is highly regarded in Hungary, and there are many monuments and roads named after him. Also, “Attila” is a common male first name in Hungary and Turkey.

While in Hungarian, Germanic, and Nordic tales Attila is depicted as a powerful and wise warrior, he was portrayed by the Romans and Greeks as a merciless destroyer and an enemy of civilization, and he is more commonly represented as such in Western art and literature. For example, Dante Alighieri puts him among the violents in the seventh circle of hell in the Inferno, the first part of the Divine Comedy. In modern popular culture, Attila is still mostly portrayed as ruthless and he appears as such in various films, TV series, and videogames.